In her current show at Gallery Four entitled “Not Now,” Hermonie Williams uses an interplay of minimalistic sculpture, graphite drawings, and shadows to explore facets of mental health as anxiety and depression. At first glance, her pieces feel understated, but within the dimmed lighting of the gallery, they succeed in carrying an introverted weight that stems directly from Williams’s simple, piercing manipulations of detail.

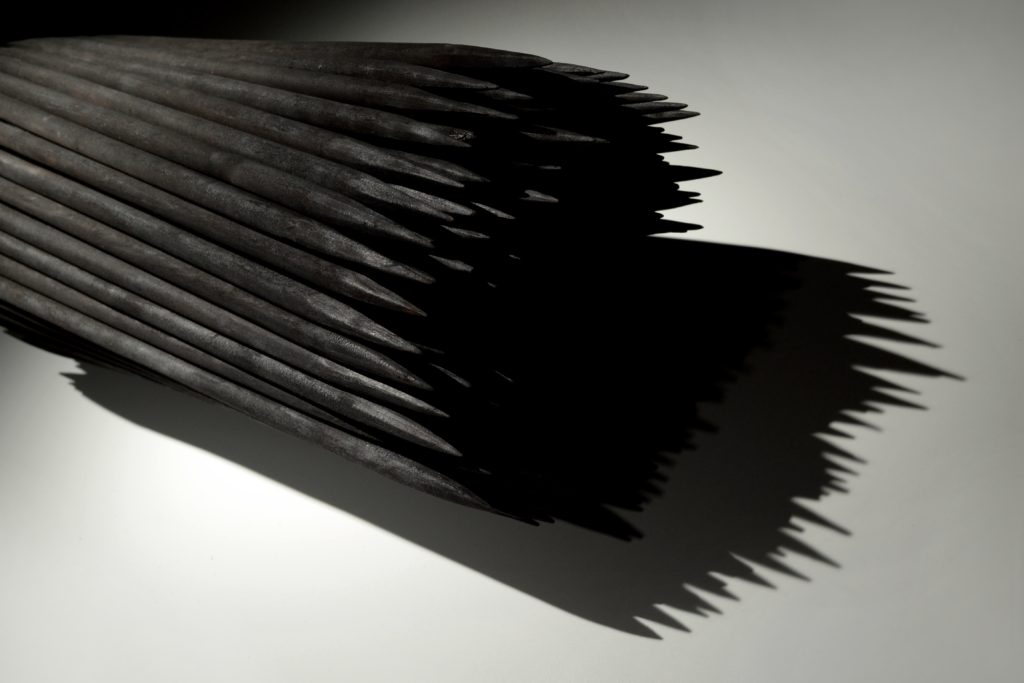

Near the entrance, a sculpture comprised of two twisted cylinders made of charred wooden spikes, sits on a pair of white tables in the first room of the gallery. Its title, “Suttee, ” refers to the obsolete Hindu ritual that required a widow to throw herself onto her husband’s funeral pyre or suicide via other methods soon after his death. The piece evokes the look of a pyre with its pointed, bunched wood, but its curvature adds a bodily element to it. That implied presence not only alludes to the human suffering its name signals, but also relates to the larger themes Williams grapples with in her text: the weight of internal anguish and finding a means to express it. In this and similar works, Williams uses fresh methods to challenge the materiality of the wood. Usually far from malleable, the wood appears able to twist and move in ways that it ultimately cannot. The sharpened, charred clusters sit spotlighted on an altar of sorts, like relics of suffering ingrained in memory through their preservation.

Williams’s polycarbonate sculptures are scattered throughout the second room of the gallery, which uses less theatrical lighting than the first. There is a subtle shift from the heaviest weight of the previous work towards something more delicately fragmented, even introverted, in nature. Curved polycarbonate beams protrude from the sparsely arranged wall and floor like distinct tendrils of anxiety quietly making their presence known and felt. One of them seems to emerge downwards from some unknown source within the wall itself. It comes to a fine point, hanging just far enough from the surface to cast a shadow.

Another piece arcs directly from the wall into the ground, echoed several feet away by a small arch rooted in the hardwood floor, entitled “After and Before.” Elsewhere, a beam hanging horizontally across two adjacent walls to create a zig-zag shaped shadow that emphasizes the absence of structure, of something more tangible and even pliable. When taken together, these works feel like manifestations of mental affliction in real time. The darkness and visual weight of the medium in conjunction with its simple, smooth forms moves the viewer to their own state of disquiet in such measured divisions of negative space.

Whatever dark levels of meditation and medium pervade the first two rooms give way to a naturally lit sort of acceptance in the third. The shades are open in both windows at the farthest end of the gallery, washing the minimal overhead spotlighting with pale sunlight. Four graphite drawings hang from the walls, and the only sculptures in the room sit comfortably on pedestals and on the ground. These pieces read as whole expressions of self, rather than pained fragments.

While another set of dark, minimalistic sculptures might have felt tired and out of place at this point in the show, Williams shows sensitivity in the dynamic range of work completed in this last room. Fifteen small, sharp pyramids are organized tightly into a rectangle on the ground, menacing in nature but pushed against the wall, quietly prevented from causing real harm. Its repeated pattern and firm attachment to the ground embodies an inner threat that is ever-present and, as the title “Might As Well Get Used To It” suggests, demands adaptation rather than avoidance. The fullness of a polished enamel square disc with a slightly convex surface, brings closure.

The crux of the show lies in this ability to depict a multiplicity of selves — both the deconstructed mind and the meditative whole — in a cohesive manner. Something new emerges in viewing pieces that are more complete, that rest between resignation and closure: a nuanced coexistence with internal struggle that has been accepted into the overarching being, but not wholly surrendered to. Such maintenance of depth is lost only in the graphite drawings, some of which almost fill the frame with swimming chaos while others are small, gridded confines with wide margins. These works feel too much like patterned representations of a disturbed mind — either “wild” and unrestrained or restricted to the point of near-emptiness — to be as impactful and varied as their sculptural counterparts.

Williams’s pieces have a dark, industrial materiality. Their curved, smooth forms are distinctly feminine, and call to mind Zachary Rawe’s description of Leslie Hewitt’s sculptural works: “Although the pieces are thin, somewhat fragile in appearance, they also occupy and control the environment through the creation of negative space.” By forcing the viewer to reconcile such pieces with their blank, expansive environments, Williams joins Hewitt in the representation of black femininity in Minimalist art as something with equal parts visual strength and structural delicacy, a sharp infusion of dark configurations into an oppressive excess of whiteness. She effectively portrays a mind seeking to be at peace with its many selves, all of which are housed within the black female body as it exists in a constant flux of contentiously white spaces. Moreover, her pieces give an authentic form to each facet of self in a manner that feels balanced; no one room or combination of works fully upstages another. Rather, the pieces gradually build off of one another to account for these emotional nuances, and their latent interconnectedness. In this way, Williams’s work embodies a psychological spectrum with compelling meditations on acute fragments of internal complexity and vulnerability.