Ginevra Shay is a Baltimore based artist. In June 2016, she founded the nomadic curatorial project Rose Arcade. She’s also Artistic Director of The Contemporary.

CA: Tell me about Rose Arcade.

GS: The aim was to create a curatorial project that was as close to my art practice as possible. In its initial inception, I thought of Rose Arcade as a sweet and small gesture; that a sincere work can be a radical act.

I’m really inspired by Jacques Tati. In an interview about his 1958 film “Mon Oncle,” a comedy about the human struggles against modernity and consumerism within a cityscape, Tati talks about this moment where Monsieur Hulot (played by Tati) opens a window in his rambling old-world Parisian apartment building to reflect a light on his neighbor’s yellow parakeet, causing it to sing. It’s a fleeting thing, but it’s also a moment that you can internalize and carry with you.

Dogs running around is a theme of nomadism in this movie, which is a point of inspiration for Rose Arcade — this freedom to act. For Tati, the dogs are able to pass through that threshold effortlessly, which is this symbolic and literal barrier between the modern world and the old world; one in which the ultimate stratification brought about by capitalism is beginning to take hold, and one that’s far smoother and more flexibly navigable. Hulot and the dogs succeed in their urban nomadism; Hulot participates in both contexts; at home in the old, and by manipulating the modern with an unwitting disavowal of its laws.

I’m drawn to the consideration for artist, site, and facilitator, that each aspect has real specificity to it. How do you find the weight of each exhibition balances artists’ works and place? Does either end up foregrounding or is the balance equal?

I don’t know that anything is ever balanced, I see it more as a concern of multiplicity, and developing a conversation between the work and the place. The things that are important to the fabric of a cityscape (like heterogeneity, multiplicity, simultaneity) also fold into the considerations of the art and the site.

For the first Rose Arcade show, Clam in the Wild, these ideas came into play. After years of walking past this arcade in my neighborhood it became a concise symbol of the area. It’s now empty, distinct, small storefronts inside a covered walkway. Outside the arcade you find rampant vacancy, crumbling infrastructure, the struggle of being a merchant in Downtown West made physical — all from poorly planned development and disinvestment in the city center. So, how do you find agency, a means to act within a place, when this is the environment you’re faced with? Is it possible to be liberated in this structure, to have a sense of the self as “wild,” while remaining grounded and connected?

I thought of Allie Linn and Margo Malter; two artists who lived in the neighborhood. This was important for the first show; while I didn’t directly articulate it to them, it seemed that both artists could address their immediate surroundings. Allie’s work addresses the relationship between history, materiality, and absence, and Margo’s work touches on the absurdity of the body, consumerism, and textiles.

Can you talk a little bit about the following show, Occhio Pavone, as well? Did that show have a similar development, or did the logistics of bringing the show to Italy change the way you were able to manage the artist pairings?

This process was a little different than Clam In The Wild. For Occhio Pavone, the title, and the writing came at the end like before. This show was still informed by conversations with the artists and considerations for the space, but the work was already made and I had no idea what the space was going to be! Hahaha. I knew I was going to Florence and that I wanted to bring some work over for a show, but I didn’t know where I was staying, what kind of space I would have access to, or even what artists I would meet upon arriving.

So when I got there, I ended up staying in this lady’s tapestry repair shop. There was a tiny, one room apartment in the back and her studio/workshop was in the front. The studio had tons of beautiful, draped threads hanging from the walls and I was immediately drawn to her space as the site. Tying the art to the tapestry repair studio was a challenge but was resolved through the writing. Occhio Pavone translates to “peacock eye” in english, and is also a type of terrazzo flooring. Terrazzo was created in Tuscany centuries ago by laborers salvaging scraps of marble to be formed into a speckled, cost-effective flooring. It’s something I see all over Baltimore as special and beautiful and it fit right into the show’s theme. Everyone gave me small works that were ideas in progress, or editions, things that were perhaps less precious to them. In the context of this tapestry repair studio, the show became about how we observe and connect things, how things become worked, finished, repaired, and abandoned. Also, the ways in which we are or are not able to see, “A beautiful unseeing eye living only to be observed.”

There were two works in the show of masked figures, one by James Bouché and one by Luigi Presicce and two works of nude women of color, made by women of color, gazing away from the viewer. In bringing over work by Theresa Chromati and June Culp, I wondered how often nude paintings, sexualized paintings, by women of color had been shown in Florence.

María Tinaut who is from Valencia, Spain often makes work using an archive of her grandfather’s family photos. For Occhio Pavone she showed a piece comprised of six black and white photos that read like stills from a film. They show her grandfather diving into the sea, or more precisely toward the sea; and in the images he is suspended in his dive, never reaching the water. There was also one of Alexander Iezzi’s “ROSE” wax bricks in the show. For Alex, the bricks function as a funeral effigy of a New York brick manufacturing company. They’re made to be donated as “A rose for ____”; a city or a person, a memory, a time. So at the end of the show, Alex and María’s works were brought to the Arno, Alex’s brick installed in the river’s bank and María’s diver finally making it into the water.

The show sounds amazing, I’m looking forward to seeing the pictures. Are there any threads that tie the two shows together so far?

I think so: an investment in beauty, loss, and empathy. I think, beauty and death could be considered closely related because of the inherent deindividuation that both participate in. Empathy is created in giving part of oneself up, even in a small way, and this is an act of beauty.

I’m curious how your role as Artistic Director at the much larger nomadic institution, The Contemporary, colors your experience in this project. I guess I’m wondering, do you operate with the same sort of mantras (“Audience is Everywhere, Artist’s Matter, Collaboration is Key”) that that institution does?

Yes, definitely.

For The Contemporary, there’s a lot more for me to manage beyond finding a site and conversations with artists; it’s so much more than curating. There’s a large budget that has to be meticulously tracked and managed, a lot of historical research, fundraising, partnerships, managing crews, material orders, housing. It’s a really big production every time we do a project with a lot of people and countless moving parts. I’ve found that there are so many sites I’m interested in that don’t really fit for The Contemporary because they’re too small or can’t be utilized for more than a few hours, and I love curating so I felt this need to keep going.

What projects are you hoping to facilitate in the future with Rose Arcade?

The next Rose Arcade show is a work by Malcolm Peacock at Druid Hill Park called Let The Sun Set On You. It’s an action that will take place at Memorial Pool and the neighboring tennis courts. Memorial Pool, originally called “Pool No. 2,” was the first municipal pool for Black folks in the United States. Pool No. 2 opened in 1921 and closed in 1956. In 1953, Thomas Cummings a 13 year old boy drowned in the Patapsco. Pool No. 2 was too crowded and he couldn’t access Pool No. 1, the whites only pool. His death led to the integration of the pools and eventually Pool No. 2 was memorialized by artist Joyce J. Scott in 1999 as “Memorial Pool”, though it remains unknown to many residents of the city.

The neighboring tennis courts were the site of the 1948 integrated tennis match protest that led to arrests and a greater push for racial equality. The courts were also the home of the first American Tennis Association national championships, where both Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe played. Unfortunately, this historically Black area of Druid Hill Park remains without lighting at night, forcing attendees to end their evenings early. This piece is rooted in creating a space for empathy. Malcolm is looking at what this space has meant historically, what it means in our current climate, and what it could come to mean for individuals in Baltimore.

As a curator, for this project specifically, I’m interested in the ways Malcolm makes work that doesn’t aestheticize history, work that includes a public but is not performative or theatrical. I wonder can (art) actions push policy change, bring signage and markers to historical sites, and needed public facilities? These are the questions I’m curious about and I’m hopeful that Malcolm’s work can bring us towards some answers.

Without giving much more away about what the action will be, I can share this quote that resonates with Malcolm by Ava DeVernay, “I wonder if by slowing the narrative down, and making it so that every second doesn’t have something to react to, could it illicit a different collective reaction? I just want to get across the whole idea of people sinking into this. That’s the only way it’s going to work is if you stop, take a moment and watch it and sink into it.”

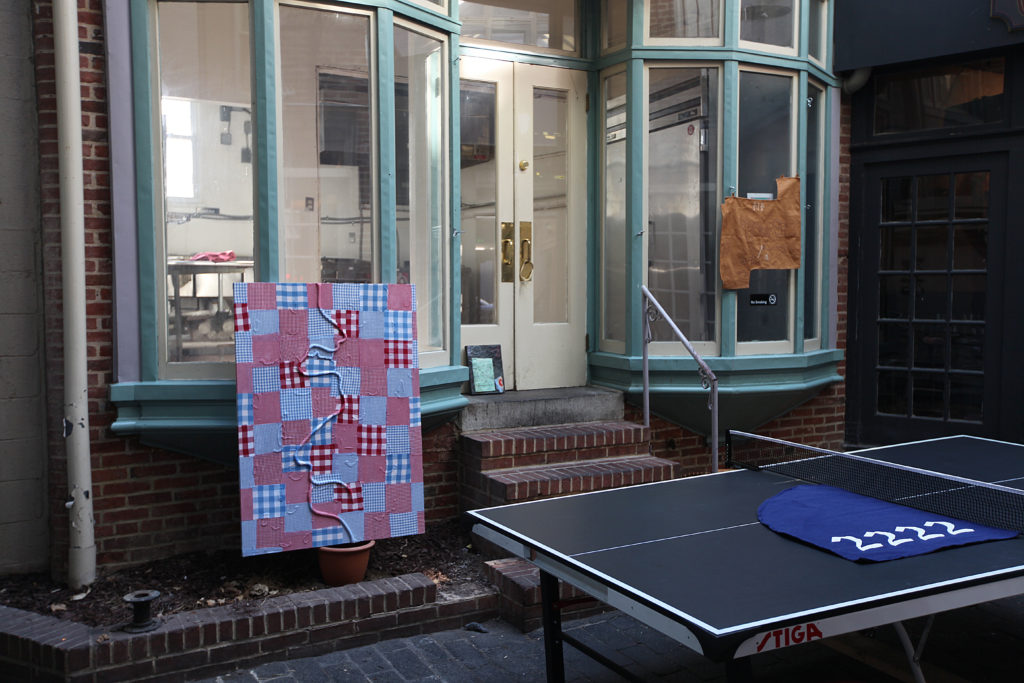

Let The Sun Set On You will take place on Monday, October 3rd at 6pm in Druid Hill Park (starting at the junction of Swann Drive and Beechwood Drive). Top photo in the article shows work by Margo Malter and Allie Linn.

Historically, a push towards deskilling (and valuing the deskilled) came paired with political implications, as it pushed the artist’s identification with the laborer by demoting the artist’s perceived agency and by including the laborer in the artist’s methods

Historically, a push towards deskilling (and valuing the deskilled) came paired with political implications, as it pushed the artist’s identification with the laborer by demoting the artist’s perceived agency and by including the laborer in the artist’s methods