“The architecture has to be an object of your memory,” Louise Bourgeois asserted in a 1999 interview with her longtime studio assistant Jerry Gorovoy. “When you summon, when you conjure the memory, in order to make it clearer, you pile up the associations the way you pile up bricks to build an edifice. Memory itself is a form of architecture.”1 In translating the domestic interiors of her youth into built sculptural spaces, Bourgeois materialized (and created space to reflect on) the narratives she had carried with her for decades. Architecture functions as both medium and metaphor in her work, so that the processes of building and remembering become synonymous.

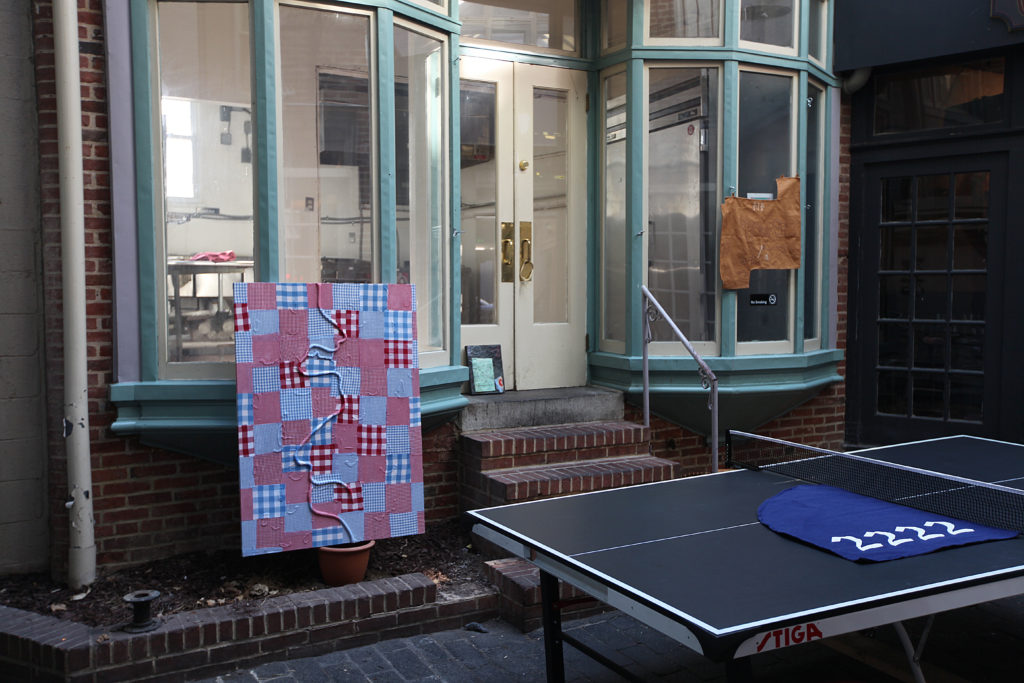

Bourgeois’s words still felt timely while walking through The Holy Ghost Goes To Bed At Midnight, James Bouché’s recent solo exhibition at School 33. Described in the gallery text as a “reconsidering of truths and values…once easily accepted” but ultimately “dismissed in adulthood,” The Holy Ghost reimagines the gallery as a stripped down, achromatic version of the Mormon temple Bouché attended as an adolescent before coming out as gay and leaving the church at sixteen. With hindsight, the remembered iconography of the original space is reimagined into a collection of artificial simulations. Once-revered objects are translated into hollow props, stripped of their function, and, at times, eroticized.

Every element within the space has been meticulously fabricated by Bouché: custom hanging ceiling-facing lights cast only a dim glow in the darkened room, and the lower half of the walls have been upholstered with grey felt. Occasional slits in this upholstery, mended with carefully placed safety pins, act as small wounds, barely discernible, but present. Paul Cowan-esque images of simplified black and white windows line the top of the walls, and vinyl decals of curtains caught in the breeze sit beneath them. Throughout the perimeter of the room are six white folding chairs, numbered one through six, teetering in various states of mid-fall. Multiple black keys hung beneath wall-mounted wax-cast flashlights provide only a suggestion of the labyrinthine expanse of the real temple.

Most captivating, perhaps, is a scaled-down replica of a traditional baptismal font sitting on the floor. True to its Mormon original, the font rests on twelve sculpted oxen, representative of the twelve tribes of Israel. One of the more publicized aspects of the Mormon church is the proxy baptism or the baptism for the dead, a practice in which a living member of the Mormon community can be baptized on behalf of a deceased person, often without their prior agreement. It is a controversial and scrutinized practice, one that can be equated with forced conversion. Importantly, Bouché’s font is empty and far too small to accommodate an adult baptism. All of the objects in the room, in fact, have been stripped of their function and rendered useless: the wax flashlights cannot illuminate, the keys indicate no accompanying locks, the windows and curtains are merely two-dimensional cartoons on a wall. These objects collectively construct an elaborate facade, aesthetically enticing but functionally frustrating.

Clipped to the lower walls are also fabricated harnesses, referencing both the bondage of imposed religion and the sexual potential of the space. In his book Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire, Aaron Betsky defines queer space as “a misuse or deformation of a place, an appropriation of the buildings and codes of the city for perverse purposes.”2 While Betsky’s 1997 work has been justifiably criticized for its rather narrow, male-centric perspective, Queer Space does provide one lens for understanding how a space of repression and condemnation might be reappropriated and reimagined as an empowering space for sexual liberation. The visual language of the remembered temple in The Holy Ghost has been adjusted only slightly, and yet the space is nevertheless radically reclaimed.

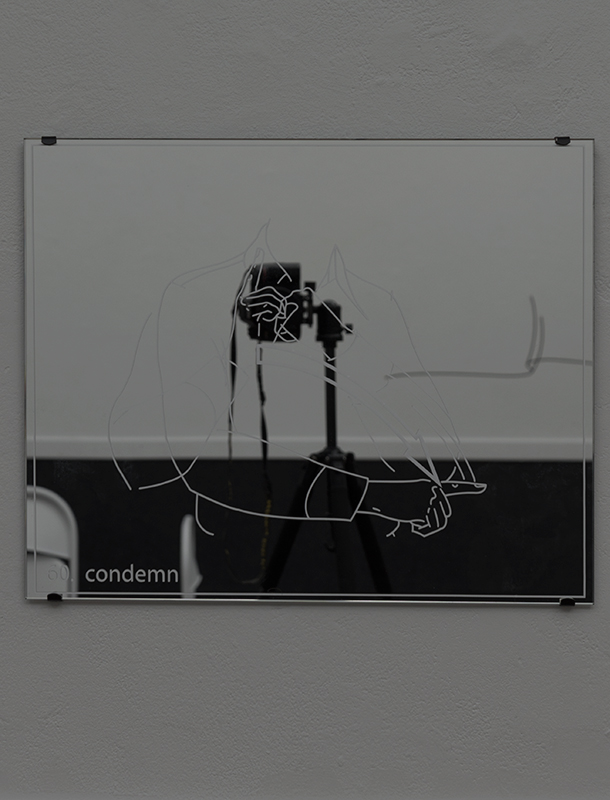

The eroticism of the room is initially subtle. Three mirrors depicting diagrams of different hand gestures, captioned “60. condemn,” “118. fornication (‘sleep around’),” and “36. bondage,” most explicitly point to sex, but even these graphics dissolve into the mirrored reflections behind them until confronted by a body. Betsky names the mirror space as “free and open, shifting and ephemeral, and yet constrained by its lack of reality,” simultaneously functioning as true reflection and intangible projection.3 Stripped of their source information, the diagrams reference both the handshakes and gestures of various Mormon ceremonies (i.e. the marriage sealing) and the body language of cruising culture. Betsky finally notes that queer space “becomes an invisible network, a code of behavior or ritualized language of gestures that traces the activities and places of everyday life,” a framework illustrated by Bouché’s co-opted and reclaimed nonverbal communications.4

The meticulous attention paid to detail in The Holy Ghost Goes to Bed At Midnight is characteristic of Bouché’s ever-thoughtful and detail-oriented practice, but the sharing of personal narrative represents a significant departure from the artist’s generally tight-lipped practice. Many of the elements of the installation are still shrouded in mystery, as the Mormon temple generally remains closed to non-practitioners, but the reflection on imposed childhood ideologies and practices is nonetheless universally understood. In the surreal, colorless mirror-world of the pseudo-temple, Bouché intertwines memory with architecture to create an immersive space for rumination and reflection.