With McLuhan as the de facto point of reference when talking about the current shift in dominant medium, it is easy to forget that much of his work specifically hinges on analyses of print, rather than film and television. His book The Gutenberg Galaxy was the 1962 goldmine of technological determinism and medium dissection that framed modern society as a product of the cold objectivity and linear qualities of the printed word.

Even at the time of writing, the rise of more participatory media signaled a shift from that once central form – so how is it that 50 years on even the worst forms of puff-periodical still manage to hold on? Despite a stumbling gallery text, Jeremy Cimafonte’s current installation at First Continent manages to point towards a frustration with this long announced “death of print.”

“Print is a dead man walking, perpetually revived by the institutions in need of it most. Pragmatic and necessary at its advent, the path towards its irrelevance would not be seen without the extensive development of entire industries around itself.”

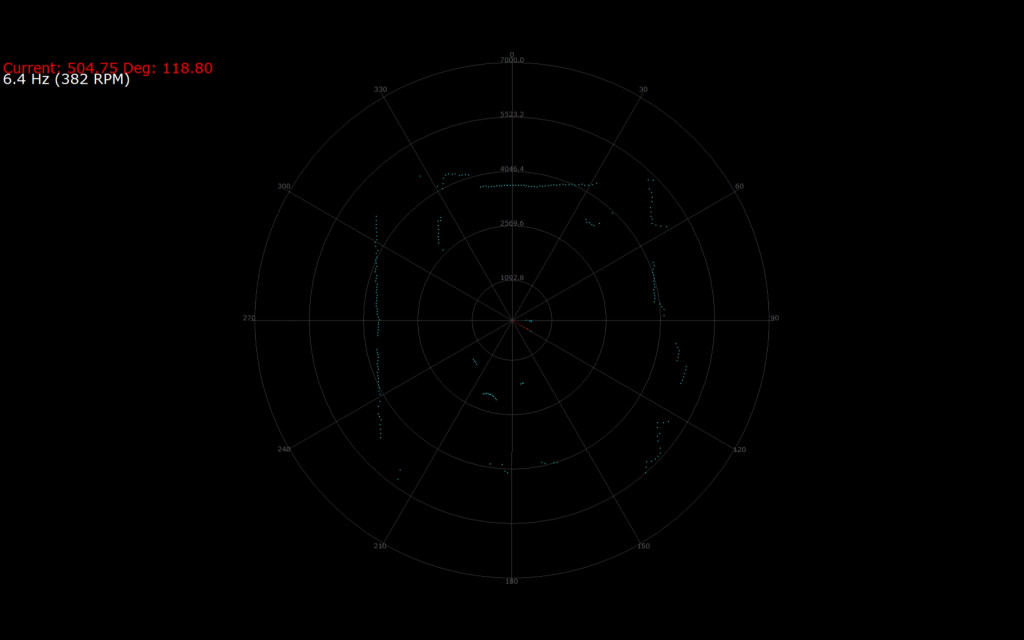

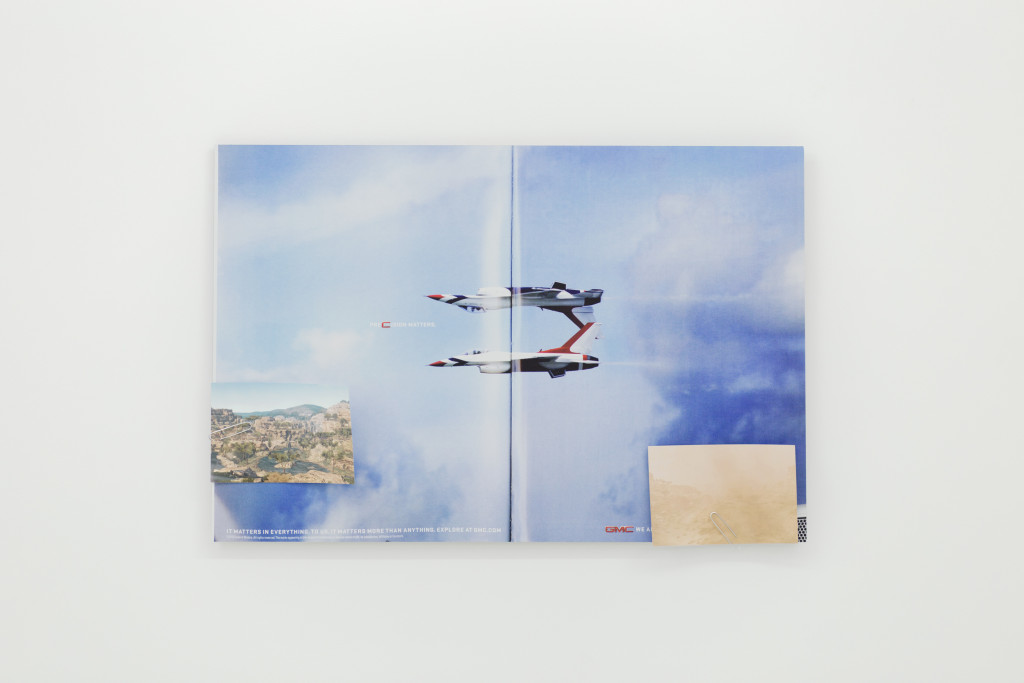

First Continent’s mirrored, fluorescent and gold space reflects four aluminum mounted prints, “slightly larger than life” reproductions of magazine periodical spreads. Each employs a casual use of magnets and paper clips to attach small, digitally rendered prints of empty (though not barren) landscapes to its surface. Adjacent to the gallery’s central mirror column stands a steadily spinning, tripod-mounted mechanism introduced as LIDAR (simple enough: “light radar”).

The LIDAR functions to gather an array of simple data points; the machine measures the distance of its laser from the first object its light hits, so while the laser spins and makes dozens of measurements per second, a monitor is able to display a primitive visualization of the space that it is in. Sort of a wobbly 2D drawing of a room.

My experience with interactive objects in galleries is pretty consistent; their attempts to grab my attention usually backfire – it is the passive objects that end up pulling me in. That said, the very presence of the machine goes beyond the role of gallery plaything by referencing a tradition of work by Harun Farocki (arguably the most important politically driven artist/filmmaker leading into the 21st century), Hito Steyerl (in her work such as How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File), and the high stakes conversation surrounding non-human observation.

That work reliably orbits the real questions in ethics of the military industrial complex. Here, there’s something perhaps less sincerely concerned, i.e. less a sense that the subject has something at stake. The LIDAR’s presence gestures towards a self-proliferating industry, one that doesn’t actually require the support, the gaze, or even the presence of a human audience. Perhaps the only sensitive reading of this arrangement is the LIDAR’s placement next to a mirror, revealing its inability to properly “see” itself in reflective objects. That said, this reading seems anthropocentrically defensive – a position that I’m not sure Cimafonte believes in.

The magazine spreads depict the most exploitative and manipulative methods of image production in advertisement, so it is easy there to follow his critique. An ad for Skecher’s shoes announces its new moisture wicking technology by cutely proclaiming “CLIMATE CHANGE” while a GMC ad shows military jet planes frozen in the midst of a flashy flight maneuver with the text “PRECISION MATTERS,” playfully sidestepping the destructive purposes for these machines. However, perhaps the real depth to Cimafonte’s arrangement of reproduced objects is that the formal language of these images is uniform. Any difference between the image selling jets (“advertisement”) and the image of a single man hiking through the woods akin to Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer (“content”) is purely situational.

The cover of nihilism that shrouds this work is similar to an attitude of apathetic critique that is easily recognizable these days, one that seems to stem from a feeling of disillusioned disempowerment. Because of that, any simple satisfaction from this display mimics the feeling of opening a new, untouched product: sweet but short-lived. Ultimately, the presence of the LIDAR is what brings this work into value by opening a conversation around complicity and finally brings up the question, “What actually perpetuates such a zombie industry?” – before (hopefully) recognizing the patterns and paradigms that obviously don’t end on the printed page.

Jeremy Cimafonte is currently on view at First Continent in Baltimore until February 20, 2016. Images courtesy of First Continent.