Deep Listening borrows its title from the practice of Deep Listening developed by American composer, Pauline Oliveros. Oliveros coined the term after a particularly formative experience playing and recording in a cistern 14 feet underground wherein as she and her collaborators played in the the echoic space it became clear they weren’t just playing their instruments, but that they were playing the room as well. Oliveros describes deep listening as “an aesthetic based upon principles of improvisation, electronic music, ritual, teaching and meditation. This aesthetic is designed to inspire both trained and untrained performers to practice the art of listening and responding to environmental conditions in solo and ensemble situations.” With Oliveros’ practice of deep listening in mind, I approached the show expecting some reverberation trail – literally or otherwise – may be of particular importance. 1

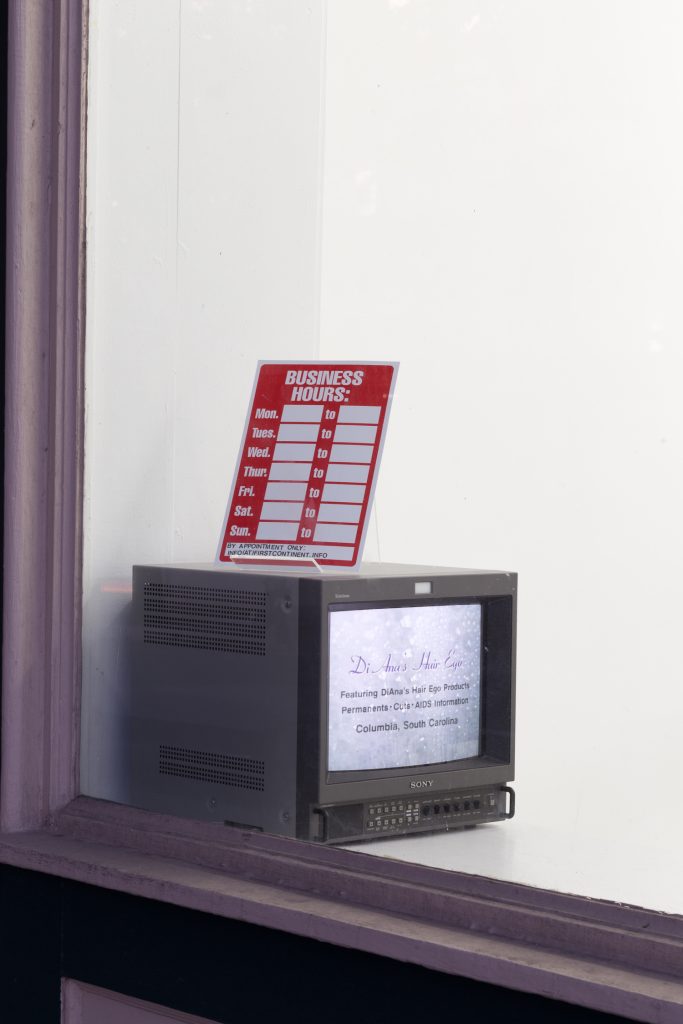

Upon entering the gallery, I immediately noticed a rather sparse arrangement, existing primarily in collections of objects on display along the window sills. Objects including a stack of mugs featuring a comic of ‘Superwoman’ fighting off a male aggressor, a stack of Barbara Kruger postcards (Your Comfort is My Silence), stuffed animal seals, Silence = Death t-shirts, a clear plexiglas dispenser of female condoms, a business hours sign with no open hours written in, a cathode ray television with footage of interviews, and various publications. All are arranged in a manner which presents as promotional or informational – like accoutrements to some local shop or doctor’s office and expressly not-so-precious as an object intended to be viewed as art. Most of these items face out of the window towards the sidewalk, a subtle yet clear gesture acknowledging the gallery’s nonexistent open hours while revealing themselves instead to an audience of passersby.

As a person who came for an opening, I began to feel there was nothing here for me aside from fellow art going acquaintances whom I can only assume were beginning to feel a similar tinge of alienation – perhaps a similar alienation felt by those walking past busy Franklin Street openings on a Saturday night knowing nothing of the elite looking gatherings in unlabeled, mostly empty storefronts.

Free food and drink, always a welcoming gesture, were provided to sooth any weariness. The concessions included the art-opening standard plastic container of ice and beer, only in this case the amount of alcoholic beverages was equally matched by a generic flavored and unflavored seltzer option, as well as a freshly cooked vegetable stew and rice served from a crockpot. The non-assumptive quality of the free non-alcoholic drinks and vegan meal added to the sense that this space is not solely designated for such a targeted audience, but modeled to facilitate a broader, family-friendly kind of gathering. The final arrangement of objects in the room was a circle of a dozen or more folding chairs – an irksomely well accommodating amount as every seat became occupied with very few left standing once the performance begins. Once the audience was seated, looking across the circle at each other under the bright florescent lighting, I get another feeling that we, the gallery audience, are on display to one another and again I remind myself – listen Deeply.

Tegegne began reading from a booklet while standing on the perimeter of the circle behind the backs of the listeners, occasionally changing her position, moving counter clockwise and then clockwise around the audience. The presentation was impersonal and matter-of-fact. She read into a microphone, amplified just loud enough to mask sound of her speaking voice and most other ambient sound, edging on a confrontational volume but falling short at just reasonable. Over the course of approximately half an hour, the monologue crisscrosses into a web composed of interview excerpts with people involved with the space as a gallery, a rental property, and a piece of the neighborhood. The landlord, the former tenant, the curators, a client of the former business, Ben Fredrick (the realtor who is currently involved in the sale of the building), Noah Barker (the first artist to have a show at First Continent), and others all form a narrative of the buildings, past and present, as understood and experienced by each character. We learned from the landlord that the storefront is a particularly attractive space for a business because of how it sits at the corner of the intersection. We also learn that this very position which gives the space this appeal for potential buyers (the block, largely occupied by artist-run galleries, is for sale) is also at high risk of cars driving into the storefront. In a subsequent interview we learn the previous tenant who ran a hair salon in the space had to leave after the third car crashed into the building while the salon was open, making it clear the risk to herself, customers, and business was too great to remain in the location. The interviews with Abbey Campbell (artist and co-director of First Continent) reveal a tenuous relationship to the space wherein the necessary labor to bring the space up to art gallery standards conveniently serves to make the space (and surrounding spaces on the block) attractive to potential buyers. They renovated the interior with their personal finances and labor, ultimately providing a more attractive, culturally relevant, and seemingly highbrow commercial space. It is clear that no one has permanent plans. The landlord and curators share a silent and mutual understanding that this is not a permanent situation for anyone but a mutually beneficial intersection of specific interests.

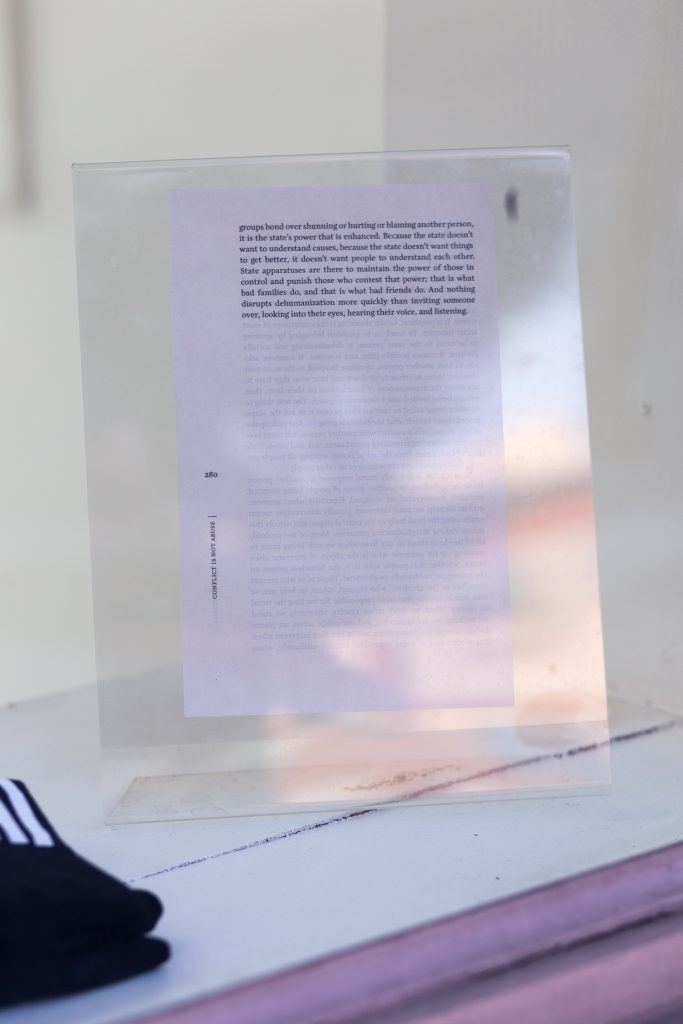

I think of the audience. On view to each other in the circle, I think how many of us live in the neighborhood, some even within buildings owned by the same landlord quoted in the monologue. To most of us, none of the information we hear is exactly new, yet having it arranged and delivered in such an organized and oddly sterile manner reveals a general voyeurism that is often overlooked (or perhaps assumed) in contemporary art contexts existing within developing urban areas. The sensitivity to acknowledge an audience beyond the transient and educated art viewer places the venue and exhibition at odds with itself; yet not because it is shamed by didactic witticisms about gentrification, but because the collected data is as much for no one as it is anyone. The narrative effectively illuminates an ambiguous triangulation of neighborhood, tenant and landlord but ceases before announcing something be done or suggesting some sort of misguided solution. Equally inconclusive is the exhibition and performance and its relationship to us, the audience in attendance: it is all too specific to be art in any other context, yet it remains ultimately inaccessible to the neighborhood beyond the few attendees. It is within this ambiguity where one may begin to hear a particularly long reverb trail if listening closely enough.

A day or two after the opening I walked by First Content to take some photographs through the windows. As I take pictures a man walks by and asks what’s going on in there? Before I can form a complete thought about how this could possibly makes sense as a nuanced exhibition directly related to this specific location and even this very interaction we’re having, he asks if people have meetings inside and if it’s some sort of art gallery. I think that’s it I reply as he wishes me a good day and continues down the sidewalk.

Bzzz Bzzz Bzzz, A performance by Ramaya Tegegne at the opening of her exhibition Deep Listening at First Continent

Deep Listening runs May 20 – June 24, 2017

Ramaya Tegegne is an artist based in Geneva, Switzerland.

This exhibition was made possible with generous support from the State of Geneva.

Photos are courtesy of First Continent.