“Spectacle” derives from Latin root spectare, meaning “to view” or “to watch,” and as such, embeds a consideration for audience before scenery. In its earliest definition, “spectacle” was considered an important element of theater performance as one of the six components of tragedy defined in Aristotle’s Poetics (alongside plot, character, diction, thought, and song).1 The description of spectacle has since expanded rapidly to include a vast array of contexts with the development of media. In Guy Debord’s 1967 work The Society of the Spectacle, its definition takes new shape, “the spectacle is simply the common language that bridges this division [between reality and hyperreality]. Spectators are linked by a one-way relationship to the very center that maintains their isolation from one another. The spectacle thus unites what is separate, but it unites it only in its separateness.”2 The evolution of an attitude towards “watching” is visible here, as well as the emergence of issues in the performance of spectacle, including the cultivated “one-way relationship” that unites the spectators by forcing them to participate and engage (within the dynamic of an isolating relationship).

It seems impossible to grasp or redefine what spectacle would be in a contemporary culture in which continuous onslaught of information and images is the norm. Society is too developed to avoid the forced “one-way” engagement, or the physical performance of spectacle. Designers persist in creating spectacles to engage or construct a so-called “user-experience.” The ubiquitous infusion of design in every aspect of society lives unnoticed, as we fanatically praise the Crystal Goblet.3 However, the real problems that are deeply rooted aren’t always evident: commodity racism in package design,4 gendered bathrooms, for-profit prisons, cultural appropriation, and even a client’s support for unethical organizations. Redesigning the website won’t solve the problem, producing more pins won’t save the world,5 so what do we do to design with social responsibility?

In 1994, Jean Baudrillard famously coined the term “hyperreality” in Simulacra and Simulation, defining the term as “the generation by models of a real without origin or reality.”6 This is to say, a sign or representation without an origin to simulate. As designed realities continue to take root in the relationship between people and world, it’s crucial to recognize the responsibility in being a designer and contributing to the cumulation of signs that assumes the role of reality. In Baudrillard’s criticism of hyperreality, he points to the blurred line between reality and simulacra as a point of danger. Being a designer in a contemporary visual culture means working directly in the medium of spectacle and being responsible for the public sphere it contributes to. Scrolling down Facebook, Instagram and Twitter has become a structural part of daily routines for not only the youth (yes, “Millennials”) but also the general public involved with business, advertising, marketing, public relations, and everything, really.

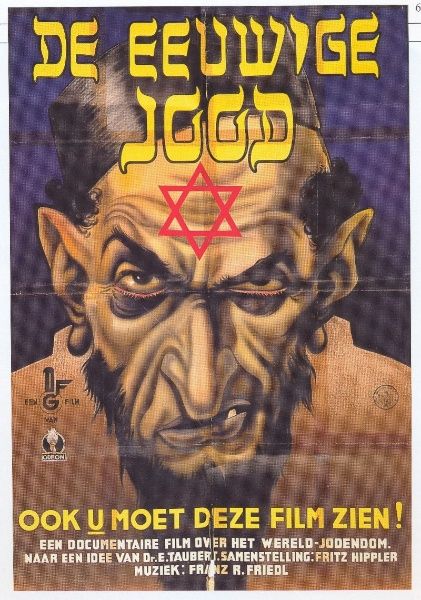

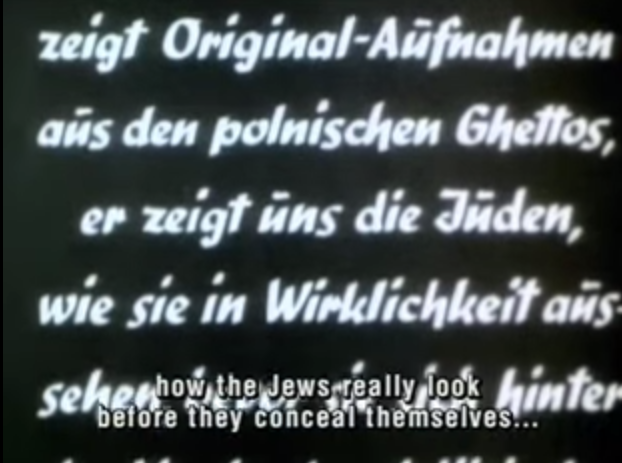

To understand design as spectacle, it’s necessary to properly place what is canonized as propaganda. The canonization of coercive techniques can neutralize those techniques’ potency, so when one studies the 20th century hypnotic brainwashing posters of the Nazi party that plastered the walls of Germany, we recognize the thin nature of those tactics while often remaining vulnerable to new tactics. The poster’s appropriate use as a medium at the time relied on its ability to be easily mass-produced and to reach large audiences, ranging from the hearts of cities to small towns in more rural areas. Realizing the power of imagery and repetitive messages, they attempted to familiarize bias into the lives of the general public.

The media phenomenon of Nazi propaganda in the 1930s serves as a benchmark for one of the most active uses of design as the driving force of political movement. Designers started to think about accessibility, mass production, and the possibilities beyond publishing literature (though Mein Kampf’s role in spreading the ideas of National Socialism to the general public in 1926 was integral). Hitler and Joseph Goebbels established The Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in the early 1930s, which aimed to “ensure that the Nazi message was successfully communicated through art, music, theater, films, books, radio, educational materials and the press.”7

For the Nazi regime, depicting the enemy as it envisioned became effortless after the introduction of sound and color in filmmaking. The Eternal Jew (1940), an anti-semitic film directed by Fritz Hippler, portrayed Jews as “plague,” comparing them to footage of rats destroying and contaminating food. At the time, similar political propaganda in the United States was depicting the Japanese. The infamously banned cartoon Tokio Jokio (1942), produced by Leon Shlesinger and Warner Bros and supervised by Corporal Norman McCabe, is one such example. In this cartoon, stereotypes and slurs take shape through a series of Japanese broadcasters and characters, depicting exaggerated accents, body language, and physical appearance—unfortunately, images that still find place in dominant ideology.

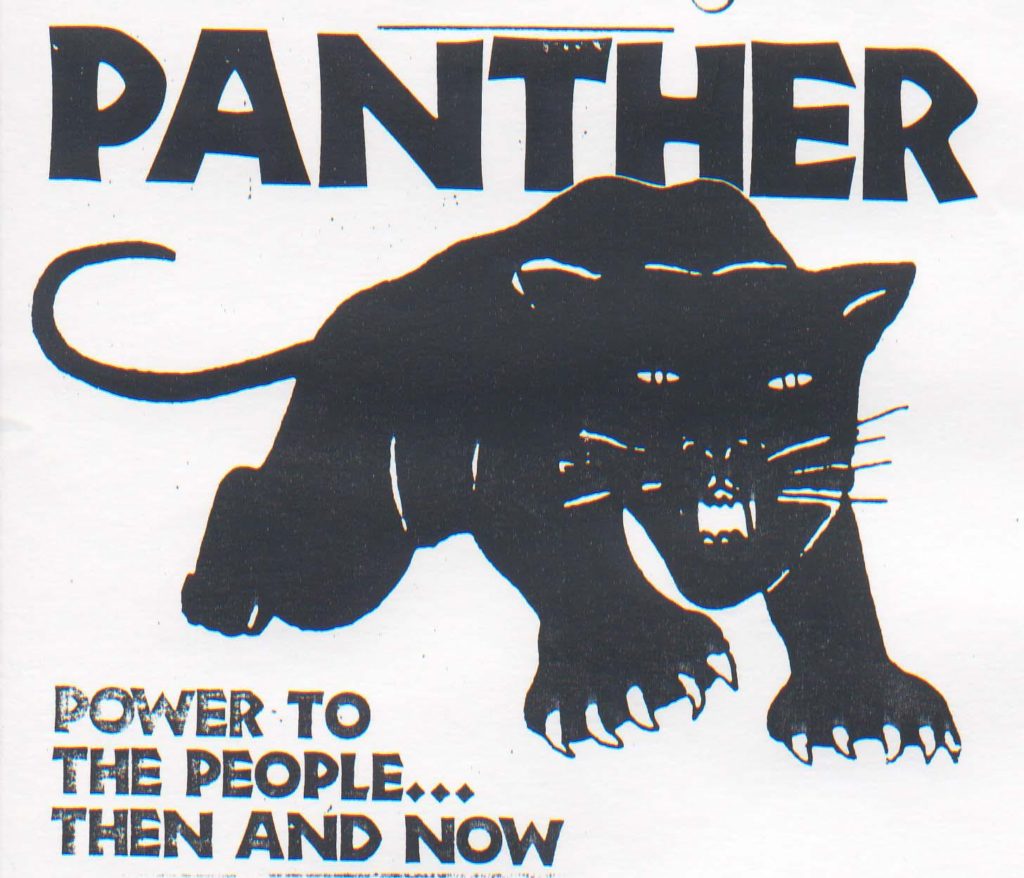

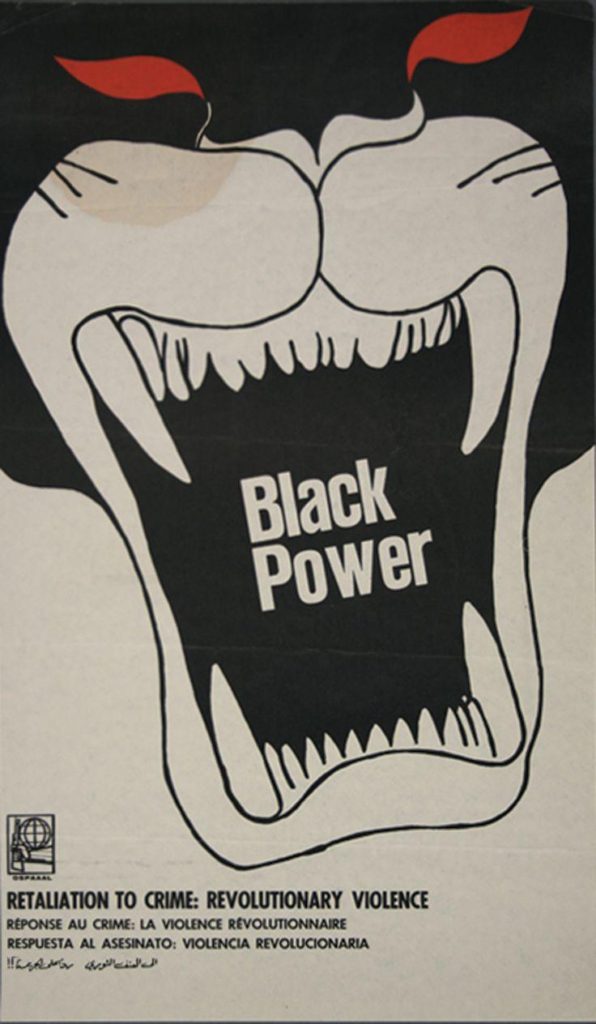

Following the US government’s role of taking part in these paradigms for ideology distribution, the introduction of U.S. private-sector propaganda was developed during the Post-War period. Driven by the self-defensive need to start a revolution against police brutality inflicted upon African-American people, the Black Panther Party was established by activists Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. Newton described their group’s symbol, the Black Panther, saying he “doesn’t strike first, but if the aggressor strikes first, then he’ll attack.”8 The group was formed specifically with the title “for Self-Defense,” and as such, used imagery that embodied the traits of a provoked force fighting against systemic and institutionalized racism and empowered African-American communities. The Black Panthers also used posters to promote and emphasize their voice, often carrying flags of the printed logo of the Black Panthers and the fist of Black Power.

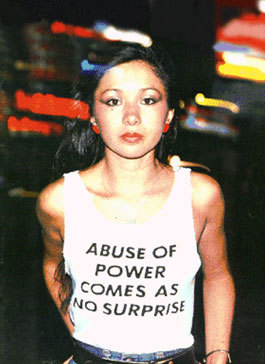

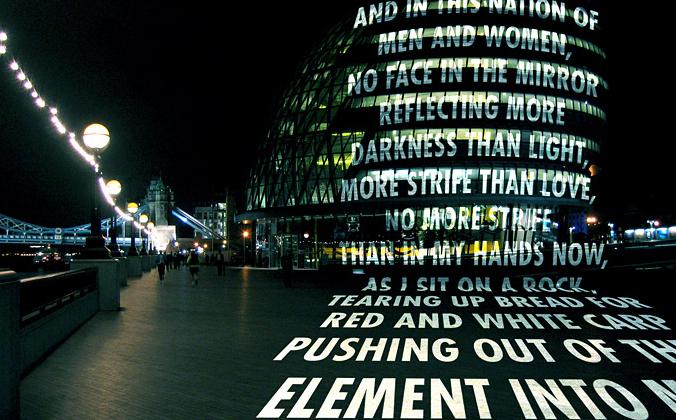

After the civil rights movement, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968, more artist communities joined in on the conversation of equality and social responsibility. In 1977, Jenny Holzer made a body of text-based work titled Truisms comprised of a series of truth telling sentences. She “typeset the sentences in alphabetical order and printed them inexpensively, using commercial printing processes. She then distributed the sheets at random and pasted them up as posters around the city. [They] eventually adorned a variety of formats, including T-shirts and baseball caps.”9

The sentences were witty, political, and thought-provoking statements that assumed a repetitive format. Using the simplest formal qualities, such as cheap colored paper and typeset Futura Oblique (as also used in Barbara Kruger’s text work), Holzer was successful in distributing her messages across the world, even gaining opportunities to project her statements in large scale onto government-owned buildings associated with the development of such techniques of propaganda.

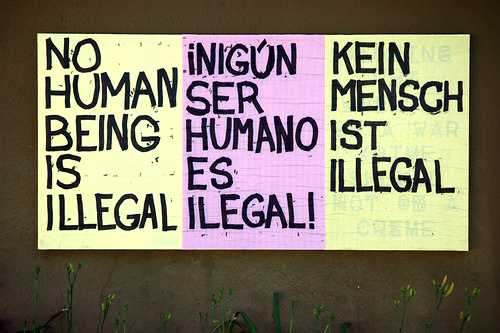

Following Holzer’s public conversations, the group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) formed in New York in the March of 1987, collecting artists around the city to create public works to rebel against silent doctors who rejected proposals for researching the causes of AIDS. One of the founding members of ACT UP, Jason Baumann, designed Silence = Death poster in that same year. “In essence and intention, the political poster is a public thing. It comes to life in the public sphere, and is academic outside of it. [The poster] is a product of collective world-making, the sort of collectivity which moves every one of us, as individuals and as a culture, and which is transformative.”10

ACT UP members agreed that when New Yorkers need to talk to each other, “there is always the street.” To open the public lines of communication, they worked on the poster to become a powerful symbol of LGBT activism at the time. As Baumann explains, most of the posters on streets are meant to be “declarative, provocative, and meant to stimulate inquiry.”11

The poster as spectacle, as a thought-provoking medium, seems to maintain relevance to this day. For a contemporary example, Ficciones Typografika is a curatorial practice that is based on collective design and is founded by Erik Brandt. Brandt is based in Minneapolis, where he curates three wooden bulletin boards outside his personal home with works submitted by designers from around the world. Brandt curates posters that illustrate a zeitgeist, or that exemplify experimentation pushing the boundaries of graphic design. A recent Nike ad that featured Serena Williams as “greatest athlete ever” with the word “female” crossed out, successfully sparked conversations within the sports community about sexism that regularly affects female athletes in not only income but also career development.12

Spectacle in contemporary society appears to open itself to easy co-optation. Its frequent use by corporations, institutions and politicians that abuse the power of spectacle reveals intent similar to that embedded in those earliest models of government deployed posters. When spectacle repeats itself and stands back to back with other spectacles on billboards, screens, and publications, those individual forms eventually cumulate a sensory overload that desensitizes spectators (the readers, the audience). Ad-funded news providers overplaying graphic videos of police brutality, overdrawing attention to unnecessary spectacles (celebrity gossip, false scandals, articles with no fact-checking), and emphasizing false hyperreal imagery (e.g. photoshopped models) deliver heavily biased, unfiltered information to spectators. Spectacle can be used in a way to provoke critical thinking and begin conversations about devalued issues, and contemporary graphic designers can take part in this process, especially in the fields of marketing, advertising, and mass media.

As the World Wide Web developed wider accessibility in the 90s, the art world also shifted towards the new medium—digital media. What the internet offered was far more shocking than the televised spectacle of the Vietnam War in the 1960s because it introduced what grassroots political efforts had worked towards for decades: an equalized agency over information distribution between individual and authoritarian forces, be they public or private ones. A notable point in this history includes the addition of social media accounts to the standard array of platforms included in corporate marketing portfolios. In this shift, one can observe efforts of authoritarian forces to mimic the grassroots formal qualities of user-generated content, especially because it is so much easier to discern (and tune out) advertisement in a field of user-created content on an internet platform than it is on other media (which often have no user contributions to contrast with). In this phenomenon, we return to the topic of Baudrillard’s hyperreality as a touchstone.

Another platform that highlights increased agency of users is the genre of Reality TV programming, in which the content consists of “users.” Media theorist Misha Kavka discusses the similar dynamic, stressing that the genre can be simultaneously compelling and threatening because of these programs’ ability to bridge the once-firm division between spectacle and experience, between the staged event and actuality, through mediated intimacy. These symptoms mark a larger shift and indicate a new global arena of power dynamics. Kavka points towards a globalized media culture in general, arguing that the public no longer recognizes the external [or, the physical] world as real. In 2002, Samuel Weber wrote in his text War, Terrorism and Spectacle, “in order for something to be a spectacle, it must, first of all, take place. Which is to say, it must be localizable. Whether inside, in a theater (of whatever kind), or outside, in the open, a spectacle must be placed in order to be seen (or heard).” In both Kavka and Weber’s arguments, they stress concerns on banality of creators of the spectacle–whether it’s blurring the line between virtual reality and reality or, from a designer’s perspective, simply publishing your projects into the public sphere.

Where does this leave us? What is the future of spectacle in a shifting media landscape? A history of spectacle reveals that it can be used to normalize toxic ideology as readily as it can subvert entrenched social structures. Currently, we’re familiar with the forms it takes in a networked public sphere to normalize and need to ask how it might instead subvert, as we have seen it function in previous media landscapes. All things we design take place out in the world, but the responsibility that comes with that task is underestimated too often. We designers are left with a vague critique, but one that might be useful: are we neither bringing in enough fresh sets of eyes, nor spending enough time thinking, nor doing enough research on history of given content? If we know we’re not considering ample time and budget to create an ethical work environment, we can look towards the past to continue this work.