Allie Linn

Estimated read time: 24 minutes.

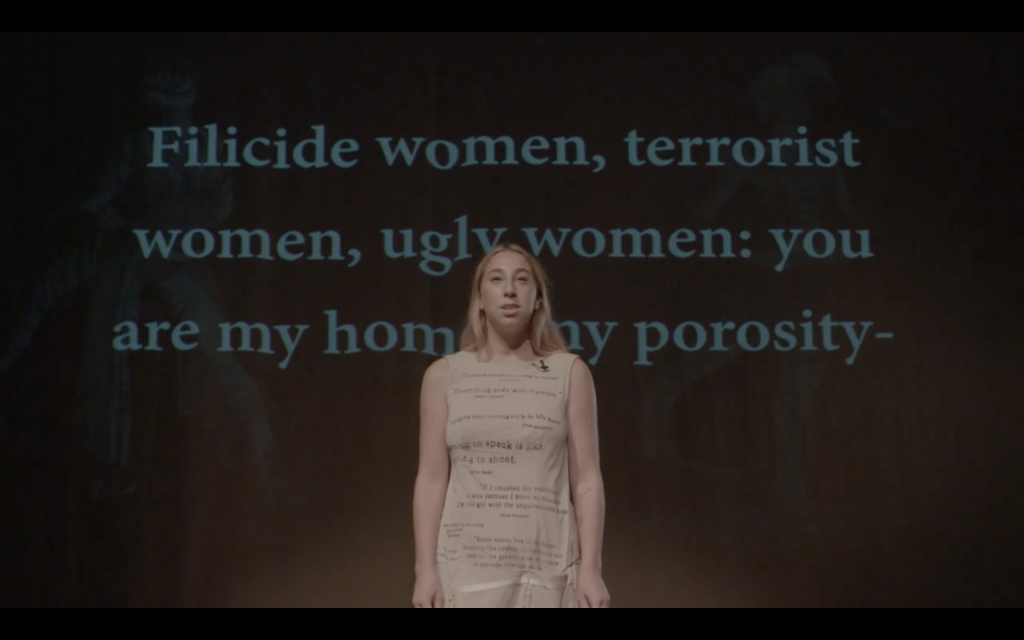

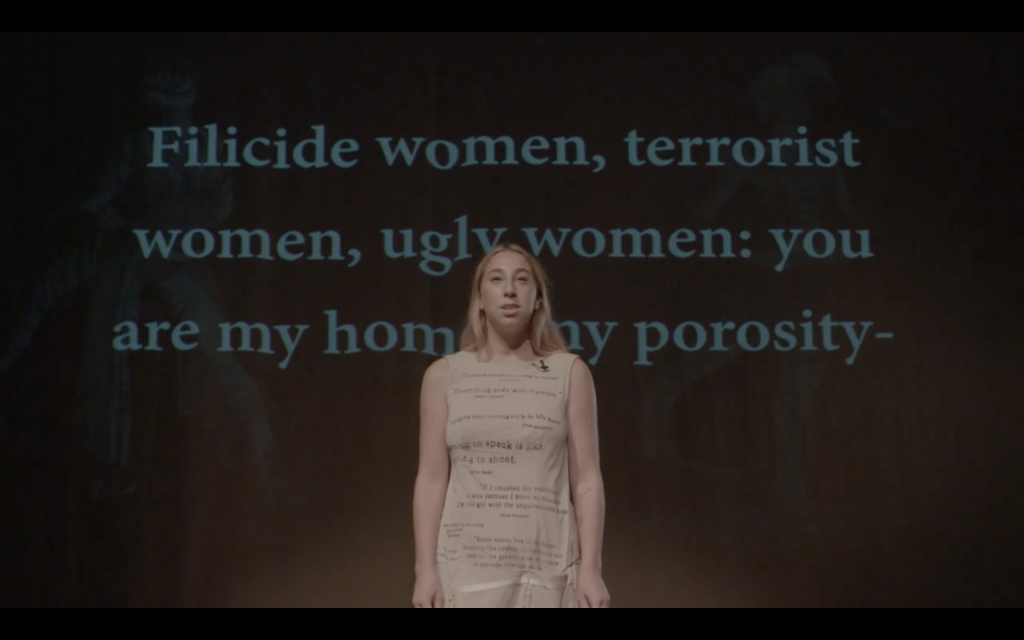

Revenge Poem (Theory of the LoFi Female), a thirteen-minute-long ballad attempting to understand the motivations for producing revenge porn and reconcile with its effects, opens with the artist, Amanda Horowitz, under a spotlight in a dark room. She describes the next steps that a target of the abuse can take, reciting instructions that are simultaneously projected on the wall behind her: “Feeling trapped? Become a porn star. Go on a killing spree. Never regret the feeling of your first kill. Embrace a journey laden in cum.” Her tone is conversational and inviting, despite the crude violence of her advice, and her deliberate lack of grief is strangely empowering. The volume of the percussive synthesizers in the background steadily rises as her message becomes increasingly urgent. “Filicide women, terrorist women, ugly women: you are my home, my porosity. Traveling through cell walls, you can escape.” Here, Horowitz first introduces the prospect of transcending the body as the ultimate means of release from a system that has birthed such a breach of trust, such a gross disregard for psychological repercussions. The target’s body has been publicized, reproduced, and manipulated to induce shame and humiliation, but the artist is not interested in the word victim.

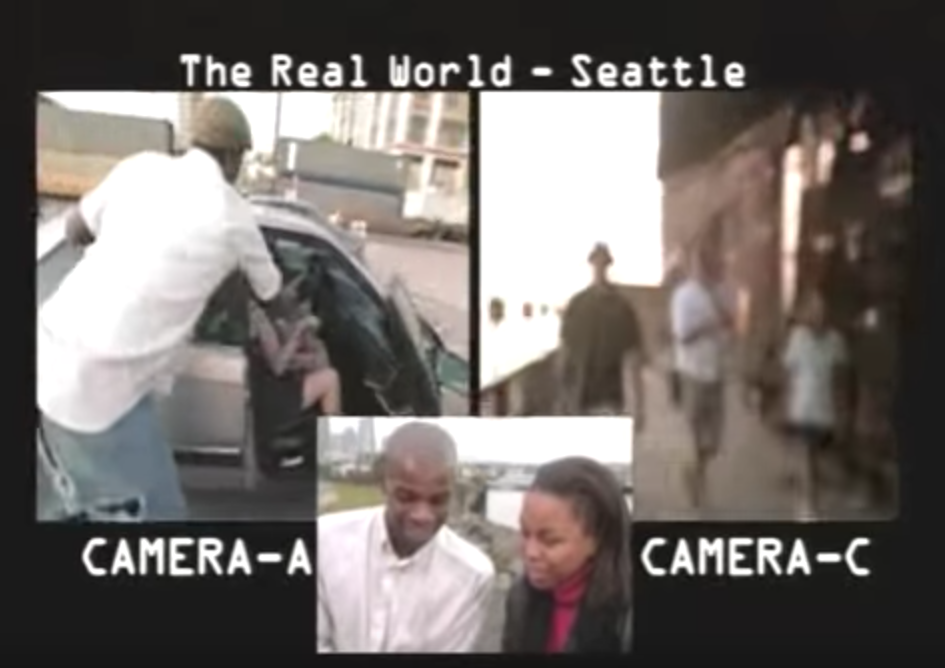

The scene changes to display an avatar of an adolescent male in a tracksuit entering the digitally rendered bedroom of a young girl. Horowitz observes the scene unfold via a projection on the wall of the room she occupies so that the view of the virtual bedroom is televised to both the artist and the audience. Like Horowitz, the male delivers a monologue, speaking aggressively but nonetheless gathering some twisted sympathy with lines like, “Flashing clothes, I’m a dashing boy/ Trapped here.” One can attempt to mine the subtle wordplay of his verses in real-time, searching for motivations for the vengeful act in lines like, “I feel anonymous when I look at it, like America chose me to make this and then I put you in a dress.” It is not completely clear who is in charge of the situation; the male seems confined to the room, monitored under surveillance, but the female can only watch his diatribe remotely and passively. It seems unsettling that this violent character would be inside of a young girl’s room for any reason, but it is understood that he exists inside of a separate, constructed world. As a digitally rendered, sometimes glitching, avatar, he seems less dangerous and more pet-like, ultimately controlled and manipulated by the artist.

Horowitz has described this project as “a perverted feminism, one that is searching for a humanity outside of sexual morals and current economic and political structures.” Using revenge porn as a catalyst for a broader inquiry into gendered power dynamics, Horowitz searches for a nuanced understanding of the impact of trauma inflicted on the female body. She uses performance, language, and drag to fluidly transition between omniscient motivational speaker, abuser, and target of the attack. It seems that even revenge porn, the quintessential gesture of misogyny, should be investigated from many different perspectives, its motives scrutinized. Horowitz has said that Revenge Poem is a “defiant slaughter of the very idea that there is a female victim,” and she explores the nebulous space between target and predator poetically and powerfully, reserving empathy for both parties.

Horowitz’s decision to eschew victimization and incite empathy, at times resulting in work that feels profane or, as she describes it, perverted, is echoed in the work of contemporaries Bunny Rogers and Jacky Connolly. Like Horowitz, Rogers and Connolly navigate the complicated implications of trauma through the inhabitation of avatars or surrogates, both physical and digital, within constructed worlds. Animated videos generated from computer graphics constitute the majority of Connolly’s practice, while Rogers and Horowitz incorporate animated avatars into larger installations that integrate craft practices traditionally characterized as feminine. The artists deviate from, and build upon, the body-centric work of Yoko Ono, Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneeman, and other feminist artists of the 1960s and 70s in order to extend the physical body into the infinitely pliable digital space of the screen. Speaking and acting through the guise of avatars, both original and appropriated, Horowitz, Rogers, and Connolly are able to translate trauma, often remembered in a fragmented manner, into a narrative structure. Whether reflecting on revenge porn, the Columbine High School massacre, or the September 11 terrorist attacks, the work investigates individual memories of universally experienced emergencies and their subsequent social and political ramifications. Recounted through a female narrator, the collective work also reflects on a broader experience of girlhood and adolescence in the dawn of the internet, identifying moments that have functioned as catalysts for premature entrance into adulthood.

N. Katherine Hayles writes that “trauma overwhelms the ability of a human to process it” and “traumatic events are experienced and remembered in a qualitatively different way from ordinary experience… Dissociated from language, trauma resists narrative.” She continues,

Experienced consciously but remembered non-linguistically, trauma has structural affinities with code. Like code, it is linked with narrative without itself being narrative. Like code, it is somewhere other than on the linguistic surface, while having power to influence that surface. Like code, it is intimately related to somatic states below the level of consciousness. These similarities suggest that code can become a conduit through which to understand, represent, and intervene in trauma.

If “conscious is to the unconscious” what “language is to code,” as Hayles argues, then the digital realm can provide an appropriate platform for processing trauma, filtering language through the virtual body of an avatar. An avatar “is generally conceived of as a passive puppet providing unmediated agency within the virtual world,” and Hayles explains the benefit of operating through this form:

The contrast between the body’s limitations and cyberspace’s power highlights the advantages of pattern over presence… As long as the pattern endures, one has attained a kind of immortality…In a world despoiled by overdevelopment, overpopulation, and time-release environmental poisons, it is comforting to think that physical forms can recover their pristine purity by being reconstituted as informational patterns in a multidimensional computer space. A cyberspace body, like a cyberspace landscape, is immune to blight and corruption.

Invincible, immortal, and immune to pain, the cyberspace body provides an ideal, neutral space for processing emotion, and because the physical body is so frequently a site of past trauma, its erasure in an artwork can represent transcendence from a psychological burden. The use of an avatar provides mediated distance for reflection on a traumatic event and further enhances the surreal and uncanny atmosphere of its aftermath. Horowitz utilizes the avatar to shift roles between male perpetrator and female victim in Revenge Poem, by way of occupying each character’s voice, while Rogers and Connolly insert themselves into cartoons and computer games, finding correlations with fictitious childhood characters.

In the writing that accompanies Revenge Poem, Horowitz describes the contemporary female as synonymous with a compressed digital image, prone to manipulation and distortion. “Like a JPEG, she has become pure data traveling through cyberspace, losing sharpness and becoming a lo-fi, genderless image.” assertion reiterates the integration of the virtual and corporeal that has been suggested by media theorists and cyberfeminists for decades, most notably by Donna Haraway in her 1985 seminal work, “A Cyborg Manifesto.” “By the late twentieth century, our time, mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism. In short, we are cyborgs,” Haraway declares.

“Why should our bodies end at the skin, or include at best other beings encapsulated by the skin?” This merger between human and machine is not meant to eradicate the body but rather explore its limitations through a synthesis with the digital realm. Maria Fernandez explains that participation in the digital world actually heightens awareness of the physical body, writing, “We need to strengthen our presence in that greatly contested [digital] realm, but with a consciousness of our bodies and embodiment. In the celebration of our union with machines, it is critical to keep in mind that technology has been an integral part of the construction and sociohistorical positioning of identities.”

Erasure of the physical representation of the body is an inherently radical gesture for an artist making work within a patriarchal structure. Artist and theorist Hannah Black has written, “The abolition of the body, [the] idea that if we were to abolish gender—if that could even be a serious political horizon—it would involve a complete re-imagining of the conceptual train of the body, an unthinking or de-creating of this idea of having a body.” This rather abstract way of thinking reimagines the potential of treating gender fluidly and, in regards to processing trauma, blurs traditionally defined feminine and masculine coping mechanisms.

For Horowitz, one of the most important reasons for utilizing an avatar in Revenge Poem is the ability to acquire “the perspective of the male cyber rapist, occupying his voice as a form of drag.” As the character delivers his monologue in the second act of the video, it quickly becomes clear that he has an extremely limited range of movement; after initially walking into the room, he stands completely frozen and unblinking, able only to jerk his neck mechanically. An inset occasionally appears to depict the artist watching the scene projected on the wall behind her. She seems to patiently wait for him to finish, wading through the hostility of his words in search of a logical reason for his violent and violating act. His words express a juvenile frustration towards being told no, and his final lines seem to depict him as a nursery school villain, simultaneously dangerous and naive.

Horowitz returns to her soapbox, now reciting her coded poem from a booklet in her hands. Occasionally, her words are interrupted by recorded protest chants and barely decipherable news and videogame clips. As she reaches the conclusion of her monologue, her sentences deviate from abstract poetry and become a more direct and confessional soliloquy:

Looking at the stolen images on revenge porn feeds, I feel a mixture of skin crawling disgust and confusion. I want to empathize with this boy, wrap my head around his motivation, turning his abuse into something substantial and greater than the senseless act, raising up its importance not as victim or perpetrator but as the forces that cast us in this technological projection. Using his attire, I want to be that girl and turn her into my bio-warrior.…

Horowitz “wants to empathize,” but she still cannot fathom the male character’s actions. In dawning his character to search for motives, she is now confronted with the possibility of also being guilty of an act of violation. The digital avatar of the male has provided space for cyberdrag and a pursuit of empathy, but it has also created discomfort and agitation. “Am I the cyber rapist?” Horowitz asks, momentarily pausing from her script, seemingly lost in the question. The video closes with a kind of duet; the male calls out the phrase, “Because my girl knows how to feel,” and Horowitz echoes, “Because I know how to feel.”

Revenge Poem was shown in Baltimore in December 2015 as part of i <3 my emergency, a two-person exhibition at Springsteen Gallery showcasing the work of Horowitz and Nandi Loaf. A group of sculptural objects by Horowitz accompanying the video are collectively titled Cloak of Earthly Objects. Three puppet-like sculptures sit on the ground, and vinyl text on the walls behind the figures display various poems by the artist: “A war is waged on/ Your pockmarks/ Your puberty/ Your butterflies in history,” and “You are a hysterical monster/ We shall never have to move,” and “Tidy up 9-1-1/ Look at the nice girl/ Standing by the airport/ Pantomiming typhoons.” The gallery text describes these works as a collective “multifaceted hyperobject of [the artist’s] experiences of 9/11.”

In a subtle nod to Revenge Poem, Cloak of Earthly Objects also uses surrogate bodies to act as exterior vessels for processing trauma. However, the surrogates have now been realized as objects and brought into the physical world. Importantly, each puppet is fully functional and can be entered; they are shells of a collective memory waiting to be manipulated by the user. The exhibition seems to reflect less on the actual events of September 11 and more on the implications of a post-9/11 world, fraught with anxiety, suspicion, and the subsequent increase of discrimination towards non-Americans and immigrants. Brian Massumi explains:

The immediate shock gave way to lingering fear, relaying the danger into a remainder of surplus threat. 9/11 was an excess-threat generating actual event, which has perhaps done more than any other threat-o-genic source to legitimate pre-emptive politics… An event where threat materializes as a clear and present danger extrudes a surplus-remainder of threat-potential, which can contaminate new objects, persons, and contexts through the joint mechanisms of the double conditional and the objective imprecision of the specificity of threat. Threat’s self-causing proliferates.

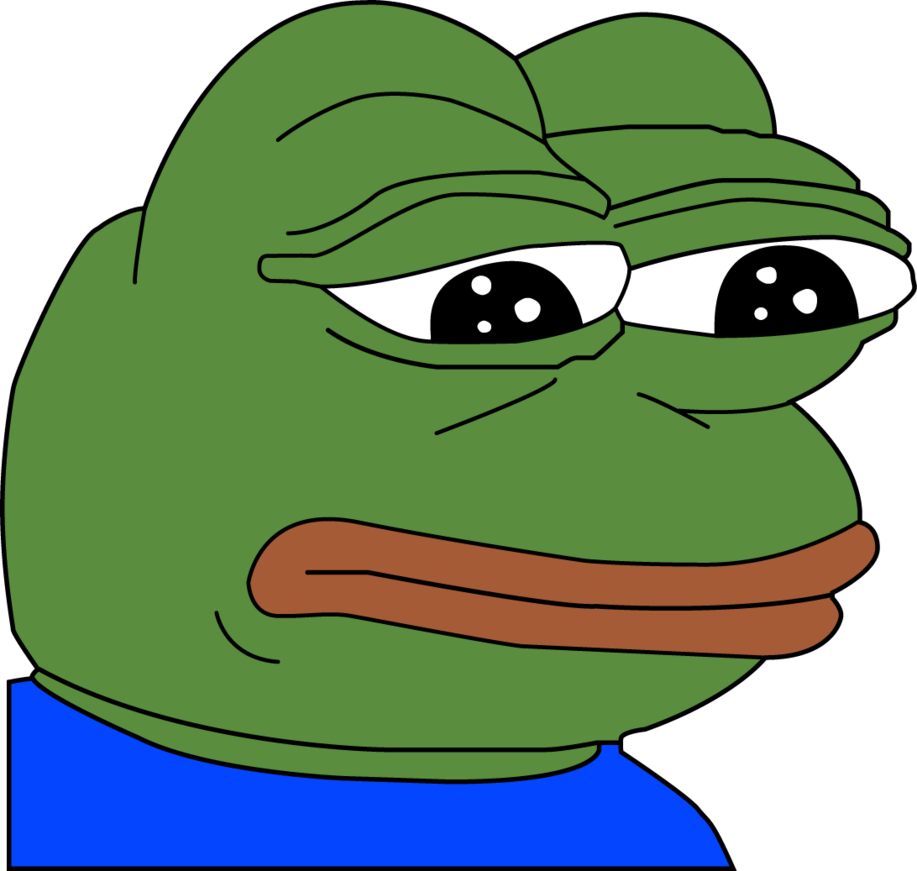

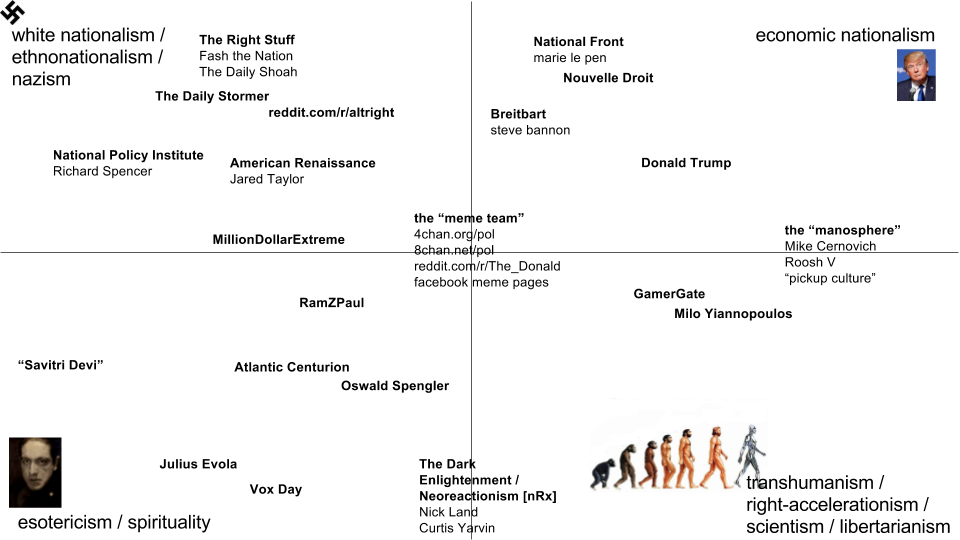

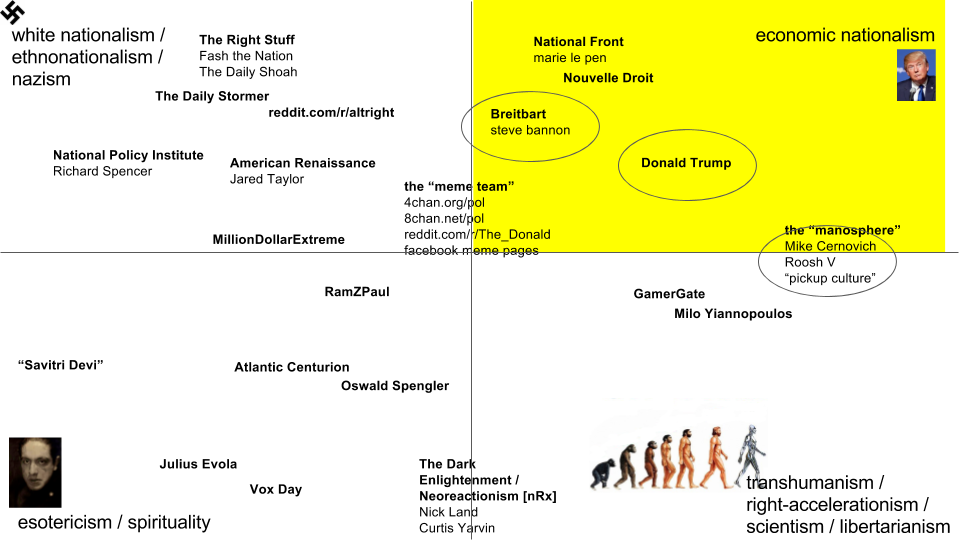

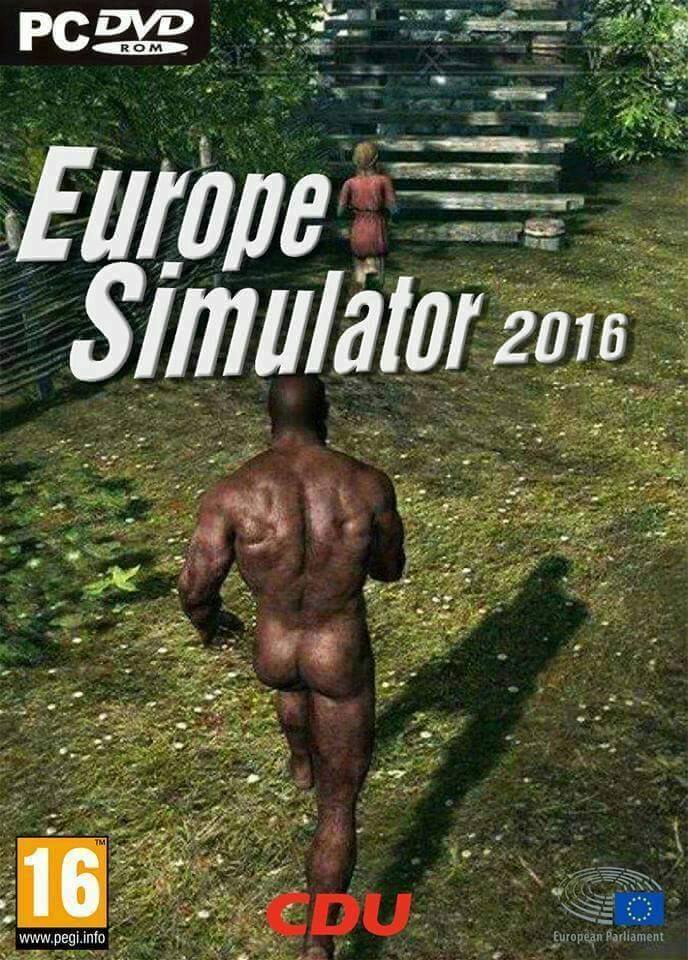

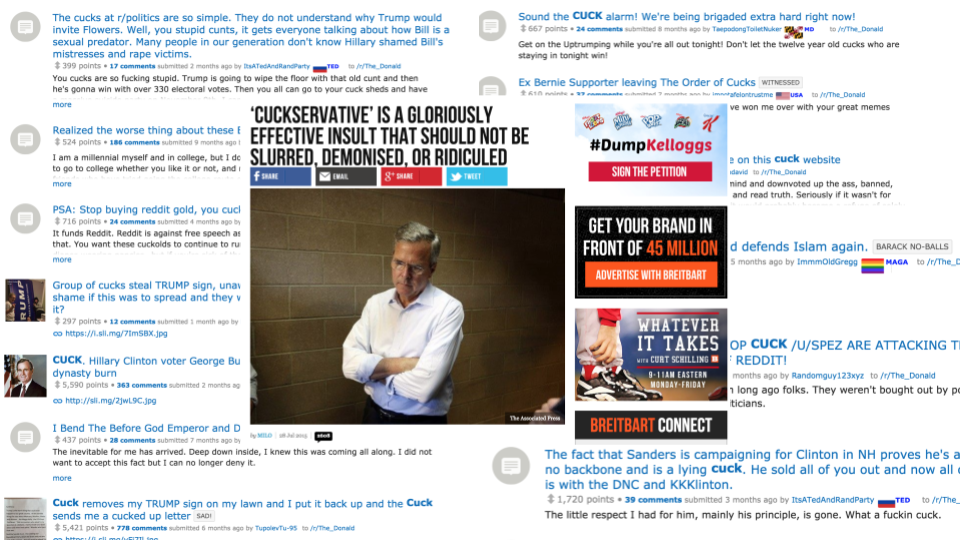

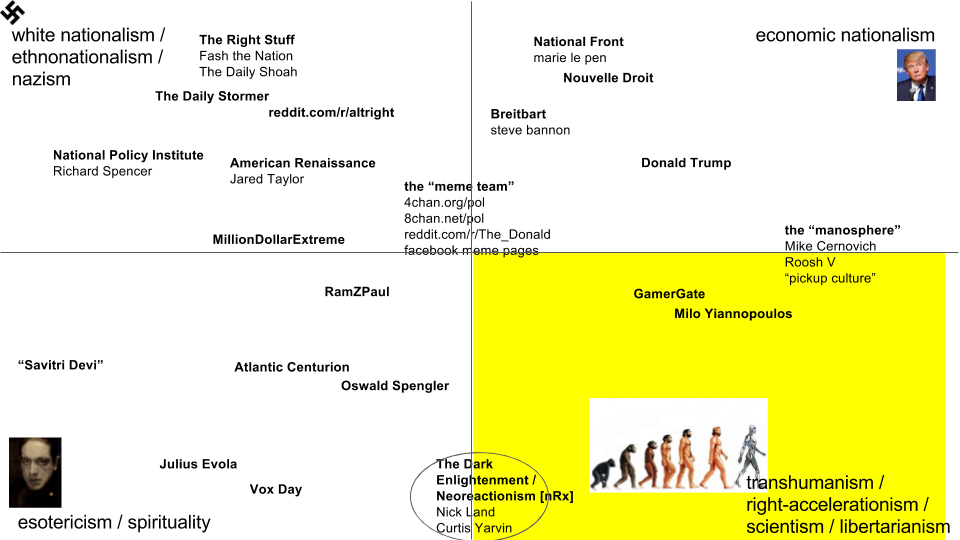

The first puppet, or “threat-potential” object, Rubble Rock, is constructed from yellow-orange foam and is covered in tire tread marks, indexical patterns of a traumatic, and possibly lethal, event. Rubble Rock resembles a frog and even potentially references the recently newsworthy meme character Pepe the Frog. The character has been listed as a hate symbol and banned by the Anti-Defamation League, following its cooption by various alt-right and white supremacist groups. Though the artist could not have foreseen how these events would play out, the allusion to a meme reinforces the fact that Rubble Rock is a character waiting to be manipulated and changed. The artist has imbued the figure with her own memory of the psychological aftermath of 9/11 and invites the viewer to do the same. The puppet is an empty vessel waiting to be directed, but the fate of the once-innocent Pepe the Frog serves as a reminder of the dark potential such a vessel possesses. Fear and anxiety can breed hatred and bigotry, and Cloak of Earthly Objects seems to document the artist coming to this realization at the young age of nine. She explains: “I think about my experience of 9/11 as still occurring, becoming a hyperobject that consumes an entire political climate of fear and hysteria.”

On the other side of the gallery is A Buff Rose, a puppet with soft, purple felt skin, a lacy white dress, and human hair. Its eyes, eyebrows, nostrils, and mouth are beaded with hundreds of white, pink, and gold microbeads, a sock is stuffed in its mouth. Like Rubble Rock, there are signs of foul play; it seems that the puppet has asphyxiated. Horowitz’s play with language once again reemerges in the title of this character; “buff” might refer to nudity, strength of the character (despite its current frail state), or it might imply that the doll will be used to mop up the floors, presumably becoming as soiled as Rubble Rock over time. It feels appropriate that these puppets tread the line between toy and portent, as they represent an account of 9/11 through the eyes of a nine-year-old.

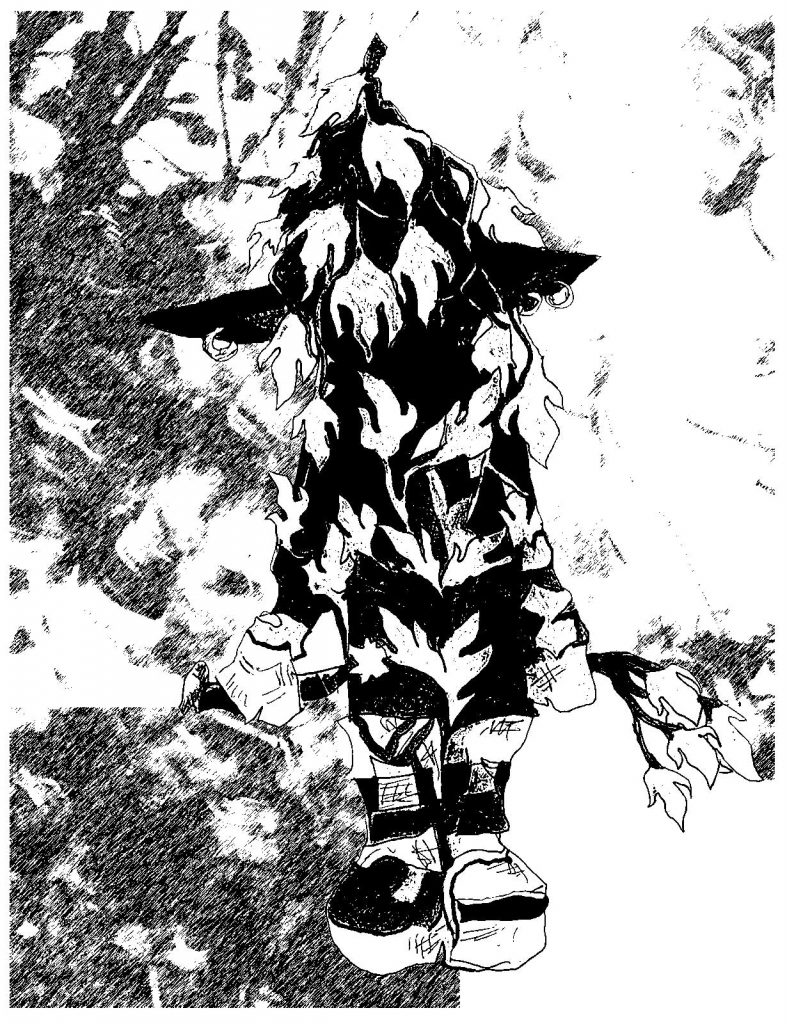

The third figure is less of a puppet and more of a sandwich board; a flat, cut-out female figure, hinged at the top of the head, wears a forest green cloak over a body covered in images of war, maps, the desert, Hummers, butterflies, and military planes. The title, Eracer Girl, similarly lends itself to various interpretations. The E-Racer is a homebuilt, single occupancy aircraft, loosely relating to September 11, but the name is also a play on email, e-waste, eBay Inc. Alternatively, the word might be a play on “eraser,” and Horowitz may be alluding to an erased childhood or loss of innocence. Whereas Rubble Rock and A Buff Rose encapsulate an indescribable feeling for Horowitz, operating more like her poetry, Eracer Girl attempts to illustrate, functioning more like a diagram; Eracer Girl is an aggregate of the media she experiences.

As self-defined hyperobjects, a term coined by Timothy Morton to describe entities “that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans…[and involve] profoundly different temporalities than the human-scale ones we are used to,” Horowitz’s marionettes attempt to encompass a wide spectrum of anxieties induced by the aftermath of 9/11. Morton would probably argue that these art objects alone hardly constitute a hyperobject, but it is interesting to begin to try to understand what the hyperobject at play might be. More so than the actual event, Horowitz is attempting to reconcile with the development of a Homeland Security Advisory System, perpetually lingering at a nervous yellow, and the surge in xenophobic and Islamophobic hate crimes. The hyperobject, maybe, is a subsequent racism that, indeed, this election season has proven to be quite rampant. “I’ve thought about those sculptures as representations that embody an abstract power network, one that spans back and forth between time,” Horowitz has said. “The puppets… can be entered and possessed, which was very important to me in thinking about them as almost voodoo objects.”

The conversation becomes gendered when we begin to consider the shared grieving within a post-9/11 landscape and the traditionally feminine characteristics this grieving is usually assigned. “When I was making those objects,” Horowitz writes, “I was thinking about an effeminized country, the use of paranoiac foreign policy as a type of domestic hysteria—a symptom once put on housewives who were trapped and repressed and now embraced as an entire national subjectivity.”

Now an obsolete medical term, hysteria came to prominence as a medical diagnosis in the Victorian era to explain a variety of symptoms ranging from anxiety to irritability to fainting spells in women. The creation of the condition, and its continued acceptance for centuries, “illustrates how Western society pathologized women’s sexuality both as a mystery and as a problem.” For many years, hysteria justified the classification of women as frail, weak, dramatic, and volatile, and, though now outdated, it is curious to see similar feelings of paranoia and anxiety regarded as heroic or patriotic through a masculine, militaristic lens. Freud later linked the condition to sexual abuse and other childhood traumas, stating that, “the subject has retained an unconscious memory of a precocious experience of… sexual abuse committed by another person; and the period of life at which this fatal event takes place is earliest youth—the years up to the age of eight to ten.” Again, the age of “eight to ten” is emphasized as an important time of transition and development during childhood, specifically girlhood; that these vital years of Horowitz’s are marred by a national crisis represents something of a twisted rite of passage. The “fatal event” that Freud describes on an individual scale is not unlike the broader “fatal event” faced on a national scale, and the two carry mirroring ramifications.

Both Revenge Poem and Cloak of Earthly Objects seek to address trauma in rather abstract terms; the artist’s writing is often deliberately cryptic and her props enigmatic. The sculptural objects, especially, seem to develop intuitively, materializing first before being completely understood by even the artist. Possessing the capacity to be entered and controlled, Horowitz’s puppets become tangible surrogates for both the artist and the viewer to impregnate with memory and emotion. They are vessels for emotional labor, concurrently laden with a universally shared experience and infinitely vacant. The puppets anthropomorphize suspicion and anxiety and surveillance, but they also ask to be played with, comforted, held. The avatar in Revenge Poem, similarly, seeks some kind of empathy, and Horowitz enters this shell, too, to search for it, but ultimately comes up empty handed.

* * *

Grappling with collective trauma through physical and digital surrogates similarly centers the work of New York-based artist Bunny Rogers. Often, Rogers masks trauma within seemingly innocuous, utilitarian objects, and she integrates her poetry into installation-based work via animated characters. Her recent installation at Greenspon Gallery in New York, Columbine Cafeteria, transforms the space into a modified representation of the cafeteria of Columbine High School, the site of the 1999 school shooting by students Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris. The exhibition, a sequel to Rogers’ earlier work on the subject, Columbine Library, is multifarious and immersive, and it feels much more fully-realized than the previous iteration. Rogers researched the event extensively and obsessively in preparation for both installations, poring over police reports, news articles, and online forums. The accompanying gallery text explains, however, that Rogers is not interested in a purely objective and straightforward translation: “The artist likewise melds fantasy and fiction with forensic data, suggesting that our experiences reside in the flux between the two.” The cafeteria tables and chairs have been painstakingly re-fabricated, while fictitious characters are implanted in the scene, generating a surreal amalgam of reality and fantasy.

Coincidentally, Rogers was also nine years old at the time of the Columbine massacre, the same age as Horowitz at the time of the September 11 attacks. Like Cloak of Earthly Objects, Columbine Cafeteria reflects on the larger implications of a nationally experienced crisis, seeking to visualize an experience that is difficult to articulate but has undoubtedly influenced the collective childhood of a generation. “Research into social absorption of the Columbine Massacre registered as a complex puzzle necessitating subjective assembly,” Rogers explains in an interview with Mousse magazine.

Nearly eighteen years later, the Columbine shootings are still regarded as a pivotal turning point in the history of school violence, forever changing the ways in which bullying, mental health, and gun violence are addressed in school. Columbine Cafeteria is an ode to a tragedy and its victims, as well as a reflection on the dawn of a new age of anxiety and fear. Like Horowitz, Rogers is interested in searching for a motivation for the horrific event, unsatisfied with the blanket accusation of mental instability. She proposes the irreverent idea that the depression and anger and loneliness experienced by Klebold and Harris are emotions experienced by all young adults.

The individual works in the exhibition demand slow interaction, and, as in much of Rogers’ work, some of the most poignant moments are found within the details, betraying the artist’s hand. Rogers has written that furniture holds the potential to become “vessels for extreme events and extremes of emotion,” noting that they, too, can become worn down and distressed. “When I look at old pieces of furniture, I kind of see a silent scream.” In the case of Columbine Cafeteria, many of these memories of “extreme events” are buried under sumptuous materials, and the objects require careful visual excavation. Their emptiness is significant.

The front room of Greenspon contains a large velvet-lined vitrine displaying outfits and ballet shoes. A standard circular cafeteria table is surrounded by fourteen purple and beige chairs and covered with apples, carved to resemble jack-o-lanterns. Various stained glass windows, framed portraits, and a cafeteria tray slide (poetically referred to as a ballet barre on the image list) adorn the walls. In the adjacent room, a tableau of an overflowing trashcan and a mop and bucket, seemingly soaked in wine, rests in a corner. An animation is projected on the wall.

The animation, Mandy’s Piano Solo in Columbine Cafeteria, portrays a 3D avatar based on the character of Mandy Moore from Clone High, a short-lived animated series centering on a high school populated by clones of historical figures.

Moore sits at a piano inside of a rendering of the school, while snow falls from the ceiling and covers the ground. The virtual space is both interior and exterior; the structure has failed to protect its lone resident, and a scantily clad Moore is exposed to the cold. There are no footsteps in the snow or other signs of life, and the chronology of the scene is ambiguous. Does she perform in the present, or has the viewer been transported back to 1999? Moore plays three Elliot Smith songs on the piano, despondent odes to adolescence, pausing only to drink from her bottle of wine.

The viewing space for the video closely replicates the animated scene; the bench in the gallery is a physical reproduction of the animated one that Moore sits on, and artificial snow also falls from the gallery ceiling, covering the floor. More carved apples, holding candles, are scattered around the floor. Moore’s world mirrors our own, and the boundary between virtual space and real space is temporarily lifted, allowing the viewer to virtually enter Columbine High School. The physical room, and specifically the piano bench, provides space for processing the tragedy while listening to Moore’s memorial performance.

Rogers seems to acknowledge the potential irreverence of inserting her own body into a tragedy she did not experience firsthand. Her decision to use a surrogate, one that can be recognized by the audience, creates a separate space for processing the Columbine massacre. Rogers can only investigate the event a decade later through online forums; her fabricated character, however, can travel to the virtual site to mourn and fill the space with music. Moore’s character seems to embody innocence and purity; she is referred to as angel in Clone High, and, in the adjacent room, she is depicted wearing a halo.

Other characters function more literally as autobiographical surrogates for Rogers. Poetry Reading with Gazlene Membrane, a video from Columbine Library, features an avatar of Gaz, the younger sister of the protagonist from the animated television series Invader Zim. Gaz is described as “the other primary, and most powerful, character… cruel, strong, and brilliant” and notably has an absentee mother, harboring childhood distress of her own. In a panel discussion at Yarat Contemporary Art Space in Azerbaijan with Suad Garayeva and Michael Connor, Rogers explains the kinship she feels with both Gaz and Joan of Arc, another character from Clone High that frequently appears in her work, including a stained glass piece in Columbine Cafeteria,

“I related to both of these characters because… they were really outwardly angry and didn’t hold back about expressing cynicism or their sarcastic senses of humor or desires to get vengeance. I think it started with realizing that the two of them seemed like sisters. Gaz is eleven, Joan is seventeen, so I saw them as sisters but also as myself at different ages.”

In Poetry Reading with Gazlene Membrane, an animated Gaz, whose head and purple pigtails are many times larger than the rest of her body, walks into a rendered depiction of the school’s cafeteria and climbs up onto a table. As in Mandy’s Piano Solo in Columbine Cafeteria, the depiction of Columbine High School is mimicked exactly, down to the measurements of the room and the positioning of the furniture. The sprinklers are running and the chairs, which have been knocked over, are submerged in water. Gaz reads from a book, Cunny Poem 1. Cunny Poem 1 is Rogers’ published anthology of poetry from 2012 to 2014, and, performed in the somber setting, lines that would otherwise seem angst-filled and melodramatic achieve more poignancy and power: “I look at you and I have no idea who you are.” “With art, feelings are clear.” “Remember this crushing day.” Rogers has successfully infiltrated a character that she has admired for some time, and it is surreal to hear her monotone voice emanate from the small cartoon mouth of Gaz. Time is compressed, fusing the Columbine massacre with childhood memories of watching Invader Zim and Rogers’ own current writing.

* * *

The use of digital avatars and constructed virtual spaces to process trauma is arguably most prominent in the work of New York-based artist Jacky Connolly. Connolly constructs characters and sets within the computer game The Sims 3 and then records real-time computer graphics to develop animated videos, a technique referred to as machinima. The films explore childhood memories through reconstructed, virtual spaces in which fact and fiction can be interwoven. On her similar and pioneering work using Second Life, Chinese artist Cao Fei has reflected that her virtual city is “not a city of magical mirror, it doesn’t restore the full present, not does it recall our reminiscence of the past. It’s a mirror that partially reflects.” Connolly operates with a similar philosophy, selectively editing and altering her childhood memories. Like Second Life, The Sims provides access to an entire virtual universe, and the user can direct his or her characters to carry out a wide variety of tasks. Connolly directs and captures in-game scenes in order to create enigmatic narratives containing little to no dialogue. Initially, playing the computer game as a child provided an escape for Connolly, and it proposed the possibility of a fluid identity within a fictitious utopia, completely under her control:

The Sims was my window onto an inaccessible realm, a fantasy theater for enacting my imagined late teen years and early adulthood—a world without school where you could drive, sleep at a man’s house, or try out his heart-shaped hot tub. I would frequently roleplay as older women that I wanted to emulate, an amalgamation of various movie and book characters and cool teens that I would see at high school. I envisioned adulthood as a world of intrigue and possibility, a release from the ensnarement of a middle school nightmare. Real life could only disappoint these optimistic projections.

The Sims remains “a fantasy theater” for Connolly, and she has explained that her work using the game “no longer enact[s] an imagined future, but reenact[s] the traumas of earlier life stages.” Her work Tales from the Borscht Belt, produced in 2016, follows a group of adolescent girls and women in and around a suburban house surrounded by rolling hills and trees. Unlike the work of Rogers or Horowitz, Borscht Belt does not point to a recognizable or historical moment as a singular catalyst for entering adulthood. Instead, the video attempts to illustrate the shared teenage experience of persistent angst and loneliness.

A female voice, presumably Connolly’s, narrates the video, reciting a poem later attributed to LiveJournal user “katythestrange.” Following the link to the user’s online diary reveals a website that has remained untouched since 2005; like so many web diaries of the early 2000s, katythestrange’s is preserved indefinitely online, capturing the sentimental and mawkish writing of her teenage years. Spoken overtop Connolly’s video, the words sound melodramatic but, at times, perplexing. “Once upon a time, long before clocks made sense, a little girl talked to rabbits,” Connolly recites, “Her worst fear was dying alone and in pain/ She built a shelter from the rain/ But one day it fell apart/ She couldn’t sing/ She’d lost her heart.” Katythestrange’s memories are interwoven with Connolly’s to create a shared experience.

Logistically, the game is an invaluable tool for Connolly, providing her with limitless access to actors, sets, and props that can be directed and transformed endlessly. The enormous expenses required for the production of a movie are wholly erased. However, beyond the pragmatism of the decision, the visual language of Connolly’s videos is extremely important to her narratives. The graphics are nostalgic, harkening to early computer games, and the repeated, algorithmically determined movements of a character’s breath or the swaying of the trees outside function as surreal temporal devices in the uncanny worlds. Connolly can seamlessly incorporate fact with fiction, retelling a narrative but allowing the story to evolve and change on its own. The rendered architectural spaces within her videos are filled with strange and dreamlike objects so that “signifiers of the domestic and of childhood (specifically girlhood) are redeployed as markers of personal identity and cultural affiliation.” This world very much belongs to Connolly, and the viewer is merely a passerby peering in.

The characters in Borscht Belt are never identified for the viewer. Most of the film depicts only small and mundane actions shared between them, though Connolly incorporates brief moments of violent or sexual acts to hint at an unseen underbelly masked beneath suburban banality. Observed from the point of view of a single character, these moments are often obscured and fleeting so that even the viewer is unable to pin down exactly what has transpired. These accumulated memories ultimately create architectural spaces that are filled with secrets and distrust. Like Rogers, Connolly is interested in the psychology of a room and its belongings:

In my scenes, the nightmares of childhood and the traumas of adolescence serve as an anteroom to hell. Anxious and foreboding nights spent in a suburban bedroom have shifted from being the context in which I was playing (as a preteen) to the subject of my film scenes. As an adult, I can now use this world for my own private film production. This is how the intrigue and possibility of the game lives on, in the sandbox world’s potential for mastery through reenactment.

Heavy rain and a foreboding, howling wind can be heard throughout most of Borscht Belt, and the ominous weather keeps the characters trapped inside of the house for the majority of the film. All of the characters are mute, and it is difficult to discern the sincerity of the relationships they share because of the avatars’ standard, vacant expressions. During one moment of clear skies, two of the young female characters relax by the pool, while a third, the youngest, slides through a slip-and-slide on an endless loop, playing alone and keeping herself occupied. Connolly’s mise-en-scénes emphasize isolation and separation, and when the same young girl later witnesses two of the female characters undressed and in bed, she is alone, observing the scene through a closed glass door. The rain falls both inside and outside of the house, as seen in Mandy’s Piano Solo in Columbine Cafeteria; once again, the architecture has failed to protect its occupants, and the young girl is witness to a mature and confusing event, rushing her maturation to adulthood.

For Connolly, working with machinima seems to provide a sense of closure. After dedicating hundreds of hours to recreating architectural spaces and settings from her childhood, she can virtually wander through these landscapes, confronting the rooms that still hold potent memories. Notably, all of the characters in Borscht Belt are female. Connolly’s characters may be unnamed family members or peers or even many different versions of the artist at various ages. The narratives reflect on girlhood and imagined matriarchy, though Connolly is ambiguous in defining the space as utopian or dystopian.

For each of these artists, the inclusion of both digital and physical surrogates provides empty vessels for processing trauma and past memories outside of the body. Horowitz uses the digital avatar as a platform for cyberdrag, finding power in occupying the virtual male body, while Rogers and Connolly infiltrate computer games and television shows from their childhoods, subverting nostalgic pastimes into an interactive stage through which adolescent anxieties can be reevaluated. The code-based language of the digital screen becomes a conduit for translating trauma into narrative, while physical props echo the role of object as vessel, imbued with poignant memories and distressing emotions. Erotic and violent narratives are explored through tender artifacts of girlhood, as in Rogers’ ribboned mops, Horowitz’s smothered puppets, and the forgotten verses of poetry from an online diary discovered by Connolly. By entering into constructed, and at times virtual, worlds, these artists explore potent, distressing memories in order to process past traumas, either personal or universal, and explore the construction of contemporary girlhood and adolescent female identity.

Images and screenshots courtesy of Amanda Horowitz, Springsteen Gallery, Greenspon Gallery, and Jacky Connolly.

(fig. c)

(fig. c) (fig. d)

(fig. d) (fig. e)

(fig. e) (fig. f)

(fig. f) (fig. g)

(fig. g)

(fig. i)

(fig. i)

(fig. l)

(fig. l) (fig. m)

(fig. m)

(fig. o)

(fig. o) (fig. p)

(fig. p)

fig. r

fig. r fig. s

fig. s

(fig. u)

(fig. u) (fig. v)

(fig. v)