After some dormancy, Post-Office is happy to announce a new series of essays gathered and published by our Summer editors-in-residence Suzanne Doogan and E. Saffronia Downing as part of their project These Essays. The pieces push Post-Office towards a broader space of non-fiction writing, and will be published Sunday mornings at 8 A.M. between August 12 and September 16.

The tyranny of the idiom is ubiquitous. Figurative rhetoric as abstract expressionism as grammatology as casual coercion as colloquialism as linguistic biopower, or something like that. The formula goes something like this: addresser employs a hermeneutic and/or ontic framing in a catch phrase to qualify what is said to addressee as being epistemologically sound.

For example, when I say take it from me I mean this object of knowledge is mine but I’m willing to loan it to you with a low interest idiomatic debt repayment plan. When I say go with the flow, I the anti-Deleuzian mean conform, buy subscription services and believe dogma. When I say to be honest, I mean every word so far has been relatively dishonest so let me interject and be the real author here ok? When I say it goes without saying, I mean duh but also let me tell you. When I say it’s a thing, I mean the subject of our conversation is actually an object that I can encapsulate and identify as super relevant, timely, but also a quaint nameless phenomena worth me naming and in such a way owning vis a vis owning up to with my last remark on the subject. You get the idea.

All of the above examples and more have their site-specific use value, but the real breadwinner is beginning a clause with the reality is. This high octane idiom is used today more than ever by politicians and pundits, anarchists and alt-righters, rich and poor alike to co-opt a dialogue and reframe it to their own ends, irrelevant to factuality or peer review. Is that a fact? Face the facts; the fact is, my alternative fact is in point of fact a fact of life. By saying that the reality is [comma so and so], the addresser is able to nullify any previously expressed conviction, sincerity, candor or validity in favor of their following argument. There’s this reality of the situation, and let me tell you how it is. My naming the reality as such gives me a hermeneutic upper hand in accounting for what we’re perceiving, and my stating that there’s this specific ontology at work where the reality is gives me an authority and groundedness previously absent and badly missing from our conversation. This idiomatic coercion is used everywhere: to set the record straight, to synopsize what really went down, to tell the truth, to lie, to defend rapists and activists and criminals and doctors and victims and tech bros and facts and fictions alike—all with the same turn of phrase.

The reality is, western states need to fight terrorism forever. The reality is, state regimes have sold ideas about freedom, liberty and rights for millennia. The moment the reality is, we jump into Jean Baudrillard’s idiomatic hyperreality, with no original referent in sight. The reality is, idioms today are employed across the board as power moves to both the benefit and detriment of their contingent, precarious employments. But where did their colloquial innocence go, and why all the syntactical fuss over winning an argument in subterfuge?

In Jean-François Lyotard’s book The Differend, he explains,“A case of differend between two parties takes place when the ‘regulation’ of the conflict that opposes them is done in the idiom of one of the parties while the wrong suffered by the other is not signified in that idiom.”1 In other words, the idiom is used to ‘regulate’ a conflict by rhetorically insinuating the non-signification of the addressee’s reality. The conversation ceases to converse and the addresser’s position in the dispute is rendered indisputable. Lyotard goes on:

In the differend, something “asks” to be put into phrases, and suffers from the wrong of not being able to be put into phrases right away. This is when the human being who thought they could use language as an instrument of communication learns through the feeling of pain which accompanies silence (and of pleasure, which accompanies the invention of a new idiom), that they are summoned by language, not to augment to their profit the quality of information communicable through existing idioms, but to recognize that what remains to be phrased exceeds what they can presently phrase, and that they must be allowed to institute idioms which do not yet exist.2

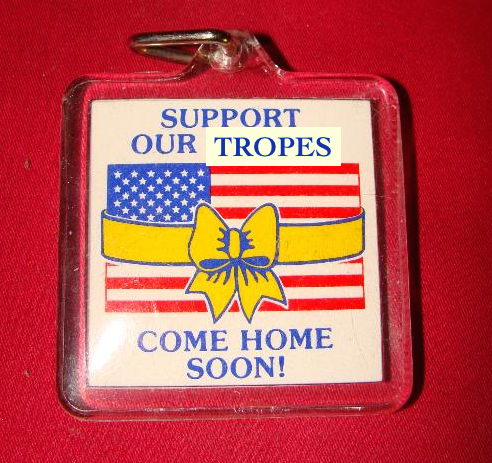

This pain is compounded by the split-second realization that the addressee can’t simply duplicate the territorialization that positioned them as addressee—they can’t simply ditto being told the reality is […] with but the reality also is […]! However, Lyotard suggests that the silenced addressee imperatively needs the impossible allowance to invent new, non-generic, DIY, hand-tailored idioms in response. While readymade, one-size-fits-all idioms tend towards coercion, idioms can also not fit—well—in their newness. In contradistinction to the latter, the emperor’s new clothes fit him very well.

Pop politics tells us to find the beef (Reagan),3 read lips (Bush),4 semanticize ontology (Clinton),5 pet the calculus (Bush pt. 2),6 romanticize poverty through shared sacrifice (Obama),7 refill the swamp with fluoridated spring water and make the USA qualitative again (Trump).8 The medium has gone from the massage back to the message.

The good news is that, like ideology, new idioms can be used for purposes other than coercion; the bad news is that the most universal of those idioms will likely sell out with age into tropey overuse. The good news is that the effect of using overabundant idioms is detectably different coming from an addresser with power and status versus an addresser without; the bad news is that, like fashion, smart phones, pop music and history, idioms seem to trickle down to average people with enough of a cogni-cultural delay that they are static, generic, drab, old news and potentially ineffectual upon arrival. It may not go without saying that we shouldn’t throw the new idiom baby out with the stale idiom bathwater, but the reality is it really depends on if that baby has prefigurative syntactico-privilege. People say not my cup of tea, not my president, when really they should be saying with non-hashtagged resistance: not my idiom.

It would be a lot easier to shoot the breeze without a house of cards.

These Essays is a periodical mini-series of non-fiction writing curated for the promotion of joy and inquiry by E. Saffronia Downing and Suzanne Doogan. For the duration of the project, one essay will be posted each Sunday here on Post-Office Arts Journal. Writing is not restricted by theme, and ranges from pop culture criticism to personal essay and material analysis. For more information or to contribute an original piece, please contact theseessays@gmail.com.