Allie Linn

The term “latent image” is generally reserved for the dialogue of photography, but the notion of a hidden or delayed image, either literally concealed or evasive from one’s memory, can apply to the experience of reading any work. In the case of Iconscapes and Year of Flowers, neighboring exhibitions that opened earlier this month at Freddy Gallery and Franklin Street, respectively, that delayed recognition becomes a connecting link between each artist’s practice. While Keith Mayerson’s Iconscapes focus on dreams and the subconscious as the starting point of the painting process, allowing symbols to automatically emerge through the guise of abstraction, the familiar, though contextually cryptic, symbols comprising David Armacost’s Year in Flowers next door force the viewer to work backwards, reading the images lining the walls to understand the artist’s personal mythology. There is a notion of anonymity within both shows; Mayerson becomes a passive liaison between subconscious and canvas, although it ultimately results in autobiographical work, while Armacost uses a visual lexicon of symbols in place of any kind of signature or statement (it’s no secret that these works are his, but nothing inside Year of Flowers says so). As the images within both shows come into focus, the sincerity of the works emerges as well.

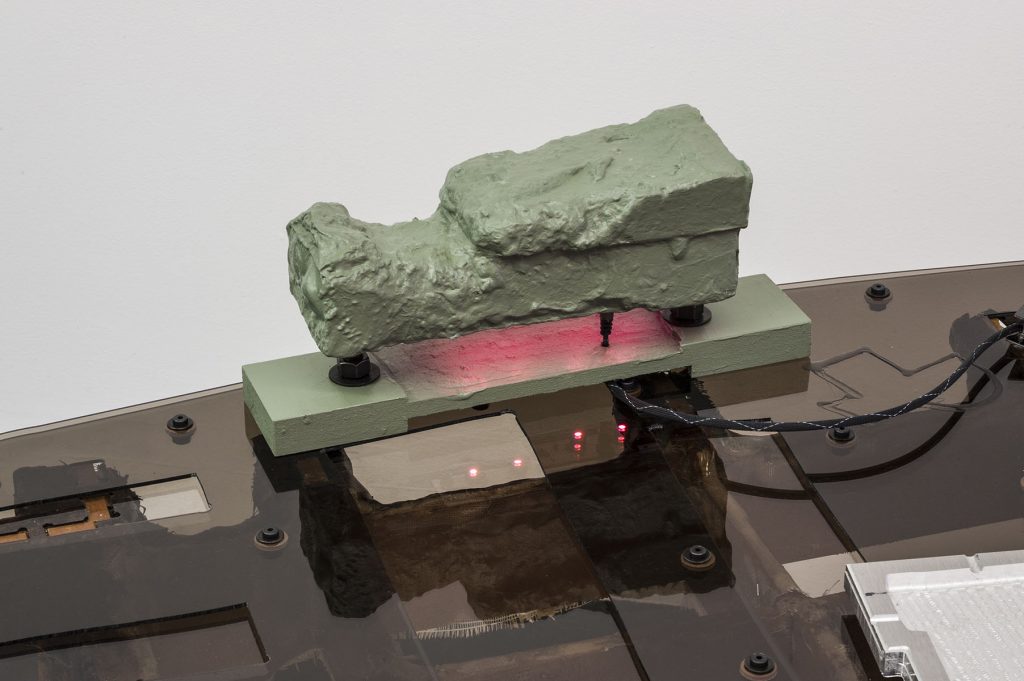

Iconscapes at Freddy Gallery presents six works by New York-based painter, and recent Whitney Biennial contributor, Keith Mayerson. Known primarily for his portraits of historical, personal, and cultural icons, Mayerson veers away from a strict adherence to linear narrative and illustrative scenes in favor of abstracted and vaguely psychedelic fields of color for the show. These works contribute to a larger series of Iconscapes that Mayerson has been exploring since the eighties as on-going attempts to “realize iconic images from [his] subconscious.” Covered in meandering, melting stews of vibrant paint strokes, the paintings fall somewhere between the works of Arshile Gorky, Joan Mitchell, and James Franklin Snodgrass, merging early abstraction and figurative abstraction with obsessive painting techniques evocative of outsider art.

On first view, the works in Iconscapesdon’t feel particularly new or innovative; they suggest a slew of references and feel vaguely familiar. The intrigue in these works, however, occurs in the crevices between strokes of paint, where the artist has inserted cartoonish eyes and ears and mouths. As these stylized body parts begin to emerge and the space beyond the surface expands, it becomes increasingly unclear which figures Mayerson has intentionally included and which ones have been imagined from the chaos of the marks.

Further clarity arises from Mayerson’s earlier writing from his 2013 exhibition “My American Dream” at Derek Eller Gallery in New York. Showcasing the same six Iconscapescurrently on view at Freddy, this exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue containing twenty-five pages of hand-written musings by the artist titled simply “Letter written on a plane to and fro Columbus.” Excerpts from this essay, perhaps the most automatic work of all by the artist, reappear in Freddy’s press release, but the passages that Mayerson has left out provide a much more direct explanation of the source of these works:

“In my thesis show back in 1988 I hung abstract works – created in part to purposely sublimate my then still ‘hidden’ (at least beyond my circle of friends) desires for other men (by breaking down forms of me and certain individuals I had secret longings for) into eyes, mouths, etc. converging over and through each other in ways I couldn’t do in real life.”

This brief insight into the origin of the Iconscapes – not a dull interest in the figurative possibilities of abstract works or a heavy-handed attempt at overly mystifying the painting process, but a poignant depiction of a young artist navigating his sexuality during the early peak of the AIDS epidemic and a subsequently extremely homophobic culture – completely changed my outlook on these works, several days after seeing them in person. As this catalogue was unaffiliated with Freddy’s exhibition, and the press release for Iconscapes references only Mayerson’s interests in the canvas as a tool for psychological navigation, it might not be fair to place Mayerson’s reflections in the context of his Freddy show, but the stakes seem so much higher, and the results so much richer, when the works’ origins are revealed.

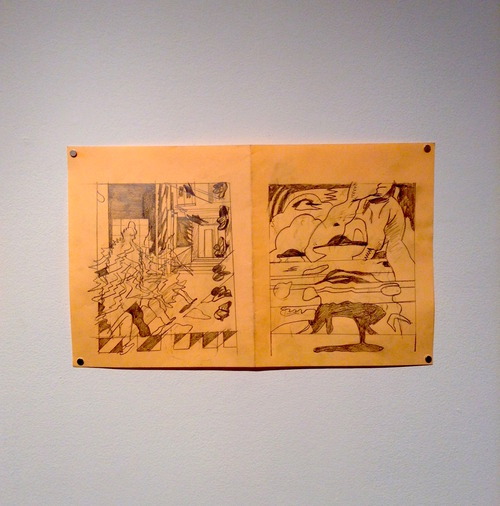

Next door at Franklin Street, David Armacost’s Year of Flowers, presented as a one-night-only event, plays with elusive imagery in a very different way, referencing symbols that feel familiar but have an undefined history. The front room of the gallery is lit only by a cluster of tea candles in front of a painted replica of Edouard Vuillard’s 1895 piece, Woman in a Striped Dress. As the first and only image visible from the street through the storefront window, Armacost’s reproduction on a cheap, cardboard-like material feels like a hand-painted sign or some a kind of DIY icon for a memorial. The reference to a recognizable painting calls into question the origin of the other pieces comprising YOF, and the nod to Vuillard informs the rest of the show: a certain softness pervades the imagery, and Vuillard’s embrace of the painting as decorative object is reconsidered in the context of the contemporary souvenir.

The back room of the gallery alludes to a funeral home, or maybe a caricature of one. The walls are draped with white cotton fabric, the floor is covered with a navy blue carpet, and the subtle fragrance of the candles from the front room lingers in the air. There is, however, a humor that pervades the space, making it seem more like a movie set for a funeral home rather than a real one: in the corner, a chair draped in white fabric painted with outstretched hands is positioned beneath a beaded picture of a bouquet of flowers, seemingly purchased from a second hand store. On the adjacent wall, a dozen small paintings centered on white pieces of cotton are casually tacked up. Resembling t-shirts or another similar souvenir object in their scale, composition and imagery, these paintings depict quick notations of quiet landscapes, more handprints, a red curtain touching the wooden stage beneath, and multiple pink lilies. These small vignettes function as brief windows into unintelligible narratives, gesturing towards the unseen landscapes that reside beyond the boundaries of the images. The repetition of the overly romantic, nostalgic symbol of the flower makes all of the scenes resonate with a certain degree of yearning while still pointing to the language of the memorial.

These paintings are really lovely, soft and immediate in their application and appearing soaked into the cotton. It is unclear, however, what the source of these moments is: Have these scenes been borrowed from postcards or other novelty items, as the Vuillard replica and framed bouquet imply? Or are they the invention of the artist, acquiring importance and history only in their repetition? It might not make a difference, but these works are appealing because of the sentiment of the marks and the mystery they exude, and in lieu of Mayerson’s writing, the absence of any kind of accompanying text to provide any clues is somewhat disappointing. The images remain fairly clouded by an unrealized articulation of their purpose. Perhaps, however, the focus is more on the performance and its conclusion – the sliver of the red curtain in one of the paintings, the bouquet of flowers that is typically presented at the end of the show, the ambiguous gesture of the hand that looks like a wave. Existing only as a one-night event, it feels appropriate that YOF reads as both a “welcome” and a “goodnight,” allowing the images within to exist as lingering, fragmented memories.

If Mayerson’s paintings become clearer and more accessible alongside the narration of the artist, Armacost’s works seem to prefer to remain somewhat ambiguous. Presented as neighboring exhibitions, Iconscapes and Year of Flowers complement one another in their varying degrees of esotericism. Armacost’s works, alluring in their form and the mystery they convey, don’t allow complete entrance by the audience, while Mayerson’s paintings, initially not very compelling, acquire interest with time. The search for the hidden image – its form, its context, its history – directs the way each artist’s work is experienced and allows for a satisfying exploration within both spaces.

(Photos courtesy of Freddy and Franklin St.)