For recently graduated international art students, the OPT (Optional Practical Training) visa presents a challenging way to remain in the United States. The visa offers a year renewal for maintaining a job in the field that you studied, but fails to acknowledge that, in the case of studio (or post-studio) artists, relevant paying positions very well might not exist. The rare administrative position becomes the expectation; actually maintaining one’s practice becomes a naïve dream.

Lian Tsai, a Taiwanese national living in the U.S. since 2008, found obtaining even one of these administrative positions next to impossible after graduating from the Maryland Institute College of Art in May 2015. In September, Tsai moved into the collectively run, live/work project space Penthouse Gallery without plans for how to handle her quickly approaching October 1st deadline.

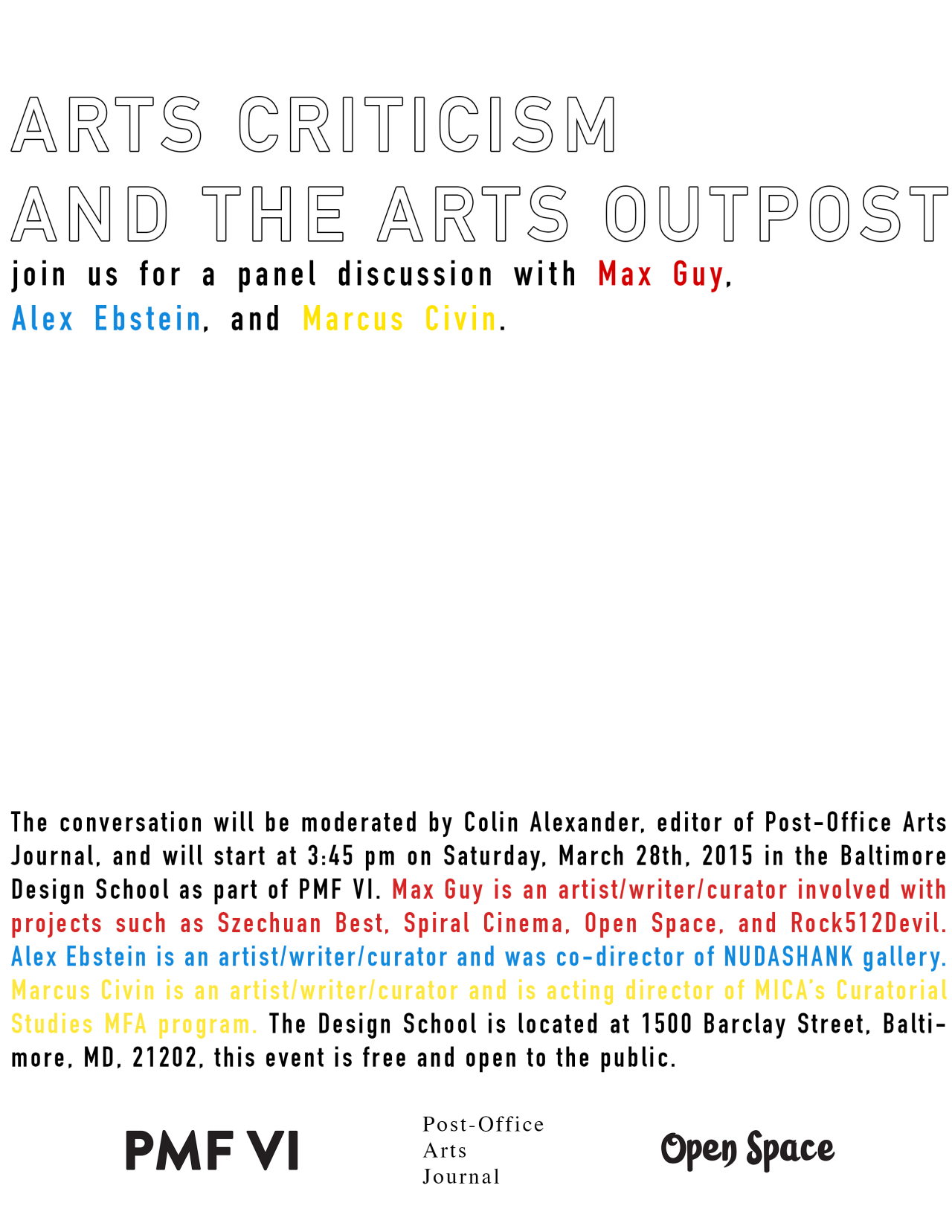

After a series of conversations between Tsai and Kimi Hanauer (a member of the Penthouse collective), the two settled on a curatorial project that would have Penthouse Gallery hire Tsai as its new Gallery Manager. Hanauer wrote a letter of hire for Tsai’s visa agent and the two quickly received notice that Tsai’s visa had been extended by one full year. As part of the contract the two wrote in this project, one of Tsai’s initial responsibilities was to organize Penthouse’s October opening. “Penthouse Gallery Presents: Lian Tsai,” documented the visa process, celebrated Tsai’s newly acquired OPT visa, and recorded the occasion of her continued residency in the United States through a durational performance performed by Tsai.

According to Hanauer, the performance went like this:

“Audience members walked in and were greeted by artist Marcelline Mandeng, who offered them a cupcake or a beer. Tsai was in the central space. She had coded a program that would translate the tone of her voice into high pitch piano sounds. She paced around the space while talking into the mic, and the program modulated her voice into those piano sounds. On the other side of the room, artist Chris Zickafoose used an actual piano to converse with Lian’s synthetic piano sounds. Lian carried a large inflatable planet on her back. She placed pumps on her hands that could inflate the planet and approached audience members, touching hands and squeezing the pumps throughout the event. This slowly inflated her planet. People sat on couches, drank beer, ate cupcakes, and blew bubbles.”

-Editor

KH: What was your experience leading up to getting the visa?

LT: It was so stressful before I talked to you. Trying to find an arts related job. It felt a lot like this OPT visa was a trap to get free labor in the U.S. for immigrants who are just getting out of college, people that have been living in the U.S. for some time and are desperate to stay. Under this visa, companies that employ us don’t have to pay us, and it’s totally legal. So I was feeling a lot of dark energy around that. When I talked to you and you came up with the idea of hiring me to work for Penthouse Gallery, I didn’t know if it would work…

KH: Honestly, I thought there was no way.

LT: Yeah. It sounded so simple, like, “I’ll just work for my friend. I’ll just make it work.” And I was running out of my grace period. So, I kind of just sent the email to my visa representative not taking it too seriously. And then she replied, said “OK,” and sent the information along. The only thing I had to change was that I had to request more hours to work at the gallery, at least 20. Which is kind of crazy if you think about it: we are legally permitted to be working for 20 hours a week unpaid.

How did you come up with the idea just on the spot?

KH: I thought, why not? I mean, it is legitimate. There is so much work to be done around here. I wish Penthouse could pay people, but that’s not how it is. I didn’t think it would work honestly, I just thought of it as a good gesture we could make, whether it worked or not. But I thought it was worth a shot, that there was a chance it might work.

So much of the artist-run activities that happen here happen without money, nobody gets paid for what they do, but then that doesn’t mean it’s not important. Why should Penthouse not be seen as legitimate? Real things happen here and it takes a ton of invisible work that is constantly being put in for no monetary return.

LT: It kind of puts us all on the same plane. Because so many of the artists here are underpaid, I don’t feel like I am being taken advantage of by the system for not getting paid. I mean, I’ve had companies tell me that they just wouldn’t pay me, but that I could work for them. And this makes me feel like I am being taken advantage of.

KH: What’s the difference here then?

LT: I guess because here, everyone is working towards a similar thing and on equal terms, and everyone is putting energy into it. And these companies definitely could pay me, they have enough going on that they could support another person for their work, but they choose not to because they don’t have to and they will have someone else trying to do it if I don’t. While this is more like we are all helping each other out. I’m putting my energy into this and you are holding me up.

KH: Yeah, it’s not a hierarchical and capitalist structure. It’s rhizomatic and none of the artists involved are really making a profit or realizing their dreams at the expense of the exploitation of someone else. This is a collective project, where those involved are mutually invested.

* * *

LT: You were talking about how not a lot of people know about what happens here?

KH: I feel like everything that happens here, or maybe just a lot artist-organized activity, is really fleeting, or you know, just not kept track of or documented well. Things just sort of happen and then they go away. And the people who are here for it know about it and experience it, but then nobody else does. And that’s kind of why it’s beautiful, why it is what it is. There is some power in that type of independence and existing outside of a traditional structure or platform.

But it’s also kind of like – what the fuck? – amazing stuff is happening everywhere and no one has access to it, almost no one can see it! The fact that even though this activity is not visible or accessible in a lot of ways, can get someone a visa, a completely life-changing thing, the fact that you can stay in the United States for another year because of this bullshit we do—it kind of legitimizes what happens here while also playing the system. We were able to use this system, that otherwise seems very oppressive, in order to legitimize work that also exists outside of dominant institutional platforms, such as art venues that exist inside of people’s homes.

LT: Yeah I like how you are talking about how it legitimizes the Copycat venues [live/work warehouse space in Baltimore], it is proof in a way. Like a medal.

KH: Exactly. But why do we have to feel like we’re playing the system? Maybe we’re not? This is a real job. The work is extremely time consuming and makes real things happen… for some reason, in my head I still feel like it’s not legitimate. I still feel like we are getting away with something, when really, “Gallery Manager of Penthouse” is a real job that has to get done. If it doesn’t get done there’d be a major Penthouse void!

LT: Why does it have to feel sort of ‘unreal,’ doing what we do?

KH: I feel so complicated about that, too, because now, I do have an art related job, that actually pays me (!) and it’s not exactly what I do in my art practice, but it is related for sure.

LT: It just makes me question my choices. Like, why didn’t I major in Graphic Design and Sculpture instead of just Sculpture? Something more “practical…”

KH: A degree in Sculpture sometimes can seem pretty useless in the eyes of the capitalist work force and the capitalist business owners when compared to Graphic Design. And why is that? It’s not as if we worked any less hours. If anything I’d say Sculpture majors are some of the hardest working, sharpest students I know.

LT: We learned how to make things happen.

KH: Exactly. But then, how do the skills we learned fit into a capitalist system? As opposed to Graphic Design, where you can just help sell people products. Our work doesn’t always lend itself to that system, and even when it does, I don’t know if we’d want it to. Maybe that’s why so much of what happens here is insular, because it mostly appeals to other artists who do the same weird shit.

* * *

LT: I think what makes events at the copycat so magical is that they bring you to another space. That’s what I was thinking when I was performing – transforming this space into a non-space.

KH: Yes, such a migrant theme…

LT: Everywhere could be my home, but nowhere is really my home. But then this place, Penthouse Gallery, lets me not worry about that and lets me create my own space without judgment or anything, it becomes a non-place for me.

KH: So, what makes Penthouse a non-place?

LT: I guess just how open and malleable it is. Its identity was built on by the people who make this place. Instead of trying to mold the artists or the people that are here into a certain ‘cool’ style.

KH: Yeah we hate “cool”!

LT: We just like to play!

KH: Somehow – your visa has legitimized all artist-run activity in Baltimore. We need you to exist now.

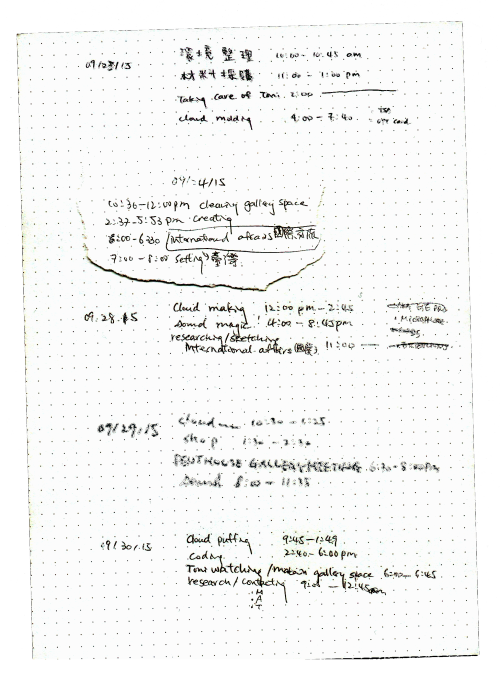

LT: It’s almost like a governmental stamp. Saying, “Ok. You guys are legit now.” The Penthouse Gallery is in federal documents now. The government knows. Even though being undocumented gives you a type of freedom, being documented makes it legitimate in a different way. They have my time sheets, my working hours, your name, and Penthouse’s name. If me taking care of Tony [the Penthouse cat – ed.], dying plastic and making patterns for my planets counts as a legitimate job to stay in the United States, then everyone at the Copycat, just living their lives, taking out the trash, doing whatever is legit…it’s a government approved job.

KH: Yes, totally.

* * *

LT: Back to my role as Gallery Manager, I have been thinking about how I could use my background to make this gallery more diverse. Sometimes I feel like people see women or non-white people as accessories. I’ve been told to embrace my Asian background more by people, like people want to be able to label me more as an Asian Artist.

KH: What happens when you are labeled in that way?

LT: I feel like when I was younger, I was really into calligraphy and other things that related more to my culture, but now that I’m here, when I’m labeled that way it just feels really limiting. It makes me into an exotic object that a white audience can look at, “she is a small Asian girl that does little Asian things.” It feels like I’m made into a fetish.

KH: Yeah I understand. I used to just not tell people I was Israeli, I would just leave it out. But now I’ve sort of started to do the opposite. And it’s not because I’m proud of that place. But I want to embrace that even though I come from this place that does terrible things and where terrible things happen, it doesn’t mean that I do terrible things. Being Israeli can also mean being a pacifist. Not that the prominent perception of Israel is anywhere near the truth, many news platforms seem to completely disregard Israel’s violent and oppressive occupation. Also, I feel like it’s important that as an Israeli, I can also be in a position to be critical of that place.

LT: Yeah I do feel like that’s something that’s easier to do when you are from that place.

KH: But also, as a migrant, when I am critical of Israel, how does that come off to people or my family members who actually live there? It’s like, well “Who are you to say that, you don’t even live here.” But, I wonder, when you are in a position where you have to constantly think about your safety, when you are living within a conflict, how can you also be thinking clearly about the morality of this or that action? In that way, migrants do have a certain special ability to be critical and thoughtful about a place. It’s because we are not really allowed to lay claim to just this or that place, you’re not really from here and you’re not really from there either.

Maybe that’s why I love Penthouse so much, it is a non-place, like you said, but its something I can finally lay claim to which also rejects that idea completely (through its non-hierarchical network of collaborators). It’s interesting that many artists take the role of protecting art platforms in general, and sometimes this means their physical manifestations, like protecting Penthouse Gallery. This is similar to my experience of being a migrant, I think. In the sense that you have to prove that this is your place, that you can be here, that what you do and how you think is legitimate, that you are legitimate… Just attempting to own that ground, to keep a space alive, becomes your work and your life. But Penthouse can’t be claimed, and it shouldn’t be—it’s inherently a huge, non-hierarchical collaboration.

LT: Do you feel that towards the United States? About criticizing the United States?

KH: In one sense I feel like, “Wow, this place is amazing.” If I didn’t live here I would’ve just been getting out of the Israeli army. Instead, I just graduated from a world-class art school, have a rad job, and am able to do projects I care about. However, while living in the U.S. has been really great to me, this place is also really terrible to many of its own people. How crazy is it that I, as someone who isn’t even originally from the United States, has had an amazing experience, while so many people who were born here, who grew up here, live in worse conditions than I would ever even experience?

LT: I have this intuitive feeling of thankfulness to the country that I struggle with. How do you feel about the thankfulness you have for America? For me, I feel kind of resentful towards it. If I feel too thankful, then I lose my power to America. It’s like they give you just what you need, nothing more, just to keep you working. But at the same time, hearing from what you just said, it is such a great thing that we are here.

KH: I understand what you’re saying, and I do feel really thankful that I live here. My brother pointed out to me recently that maybe we shouldn’t feel thankful for a government or social structure for simply doing the right thing, what they should be doing anyways. Like granting people’s basic freedoms and rights and having a minimum safety-net like a welfare program, and for not making military service mandatory so people aren’t forced to fight in unjustifiable wars. We are allowed to be critical of the country we live in and still appreciate living in that country.

Documents :

letter of offering (k. hanauer)

letter of acceptance (l. tsai)

Photos and documents courtesy of Penthouse and the artist.

Photo credit : Brandon Price.