Hedera Helix is the fourth publication as part of These Essays, a series selected by editors-in-residence Suzanne Doogan and E. Saffronia Downing.

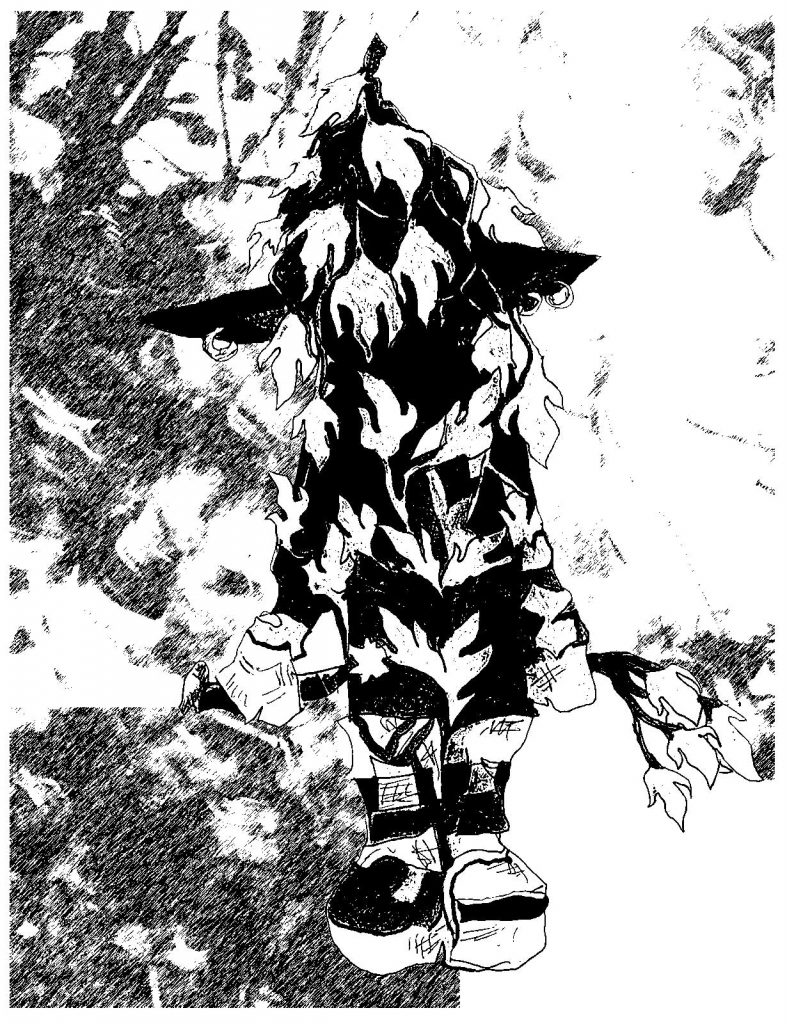

In the forest, English ivy slowly climbs a tulip poplar. The ivy spreads to envelop branches and twigs, caressing the tall tree, winding its way toward the sky above. As seasons pass, the vine’s growth engulfs the tree beneath a cloak of deep green ivy. Shaded from sunlight, the tree cannot photosynthesize. The tall tree buckles under ivy’s weight. The vine entwines the tree to death.

In the Eighteenth Century, European Colonists brought English ivy (Hedera Helix) across the ocean into the “New World.” As they moved past the boundary of mapped earth, settlers brought plants that reminded them of home. Faced with vast untamed wilderness, colonists cultivated plants they knew. “[Ivy] is so well known to almost every child to grow upon the stone walls of churches, houses, &c. and sometimes to grow alone of itself, though but seldom” wrote a British physician in 1653.1 They knew ivy; the vine had grown with them since before memory.

I wonder how ivy went across the sea. Who tended clippings of Hedera helix on the journey into the unknown? Who moistened it’s roots, shone light on it’s leaves? Elseways, was the plant brought as seed? Dried in summer, stratified through winter, then stored away in a trunk below deck to be propagated on unknown shores. Still another option is that ivy was brought by accident. The seed stuck to the bottom of a settler’s boot.

With ivy in their satchels, settlers journeyed across the vast ocean. Their desire was palpable as they gazed onto blue shores beyond. In her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit finds words for desire resting on the horizon– distant places cast in a blue hue. She calls it the blue of distance. You may long to go to the blue place far away, but it won’t be blue when you arrive. “Blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon, but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains.” Desire took the shape of blue distance as they gazed into the unknown. When they arrived however, color became green.

Hundreds of years later, forests of green-coated mammoths lined the highways of my childhood. The landscape of my East coast memory is green ivy desert. The vine spread across the wood singles of my childhood home. It coated the pavement of the abandoned lot next door. It reached toward the trunk of my backyard magnolia. Dark green, white veined, three pointed leaves are imprinted in my memory.

In Europe, ivy is part of the native ecosystem. The plant is a valuable source of food for species of wildlife. This naturally prevents ivy from invasive spreading. In North America however, where insects and animals have not evolved to eat the plant, ivy spreads to envelop forests, backyards, and wastelands. The earth longs to be covered in plants. Vigorous plants brought from distant shores take root in bare soil left behind bulldozers. Plants brought by colonists displaced native plants like colonists displaced native people, creating a new ecosystem of adapted species.

Colonists brought ivy to the “New World” to remind them of home. Now, people spend hours removing the plant from the wilderness, an effort to preserve something already lost. The vine is pulled away from the tree with a pry bar, and then cut in a wide band across the tree’s trunk using pruning shears, saws, loppers or a hand axe. The plant is then burned or bagged in black plastic and thrown into the garbage. As homeowners tear the plant from their trees, ivy continues to be propagated by garden centers for commercial sale. The rows of plastic pots come adorned with a caution tag warning buyers of invasive qualities.

In the post-industrial city where I live, the fibrous vine spreads across red brick. Brought by my ancestors from distant shores, the plant has altered the landscape of the place that I live– shaping a modern ecology where biodiversity falters and monoculture reigns. Ivy is well known to almost every child, to grow on row-homes, trees, and telephone polls. The plant has grown with us since before memory.

These Essays is a periodical mini-series of non-fiction writing curated for the promotion of joy and inquiry by E. Saffronia Downing and Suzanne Doogan. For the duration of the project, one essay will be posted each Sunday here on Post-Office Arts Journal. Writing is not restricted by theme, and ranges from pop culture criticism to personal essay and material analysis. For more information or to contribute an original piece, please contact theseessays@gmail.com.