To point is to leap from one thing to an unrelated other.

In Modern Athens, the vehicles of mass transportation are called metaphorai. To go to work or come home, one takes a “metaphor”— a bus or a train.

The gesture of “pointing,” similar to the metaphor, is manipulative; a tool used most by memesters who post captioned/captionless imagery (that I am supposed to ‘get’). The highlighting of the rift between thing and expectation is, for some, a method to be utilized for subversion—a simultaneous appeal to and embarrassing of a mass-subjectivity we often confuse as ‘the personal’. The contemporary artist points in a similar way. Or, in the exact same way (Puppies Puppies, Scariest Bug Ever, Goth Shakira).

Colin Foster presents a body of work at Springsteen Gallery on West Franklin Street; the exhibition attempts to point toward some thing as well. The objects, however, exhibit surreality because of the ignorance they express toward their own trajectories as affect-producing things. With this, while the work exhibits interesting manipulation of materials and showcases Foster’s mastery as a maker, I am going to focus on the conceptual backing of the exhibition and some of its possible shortcomings.

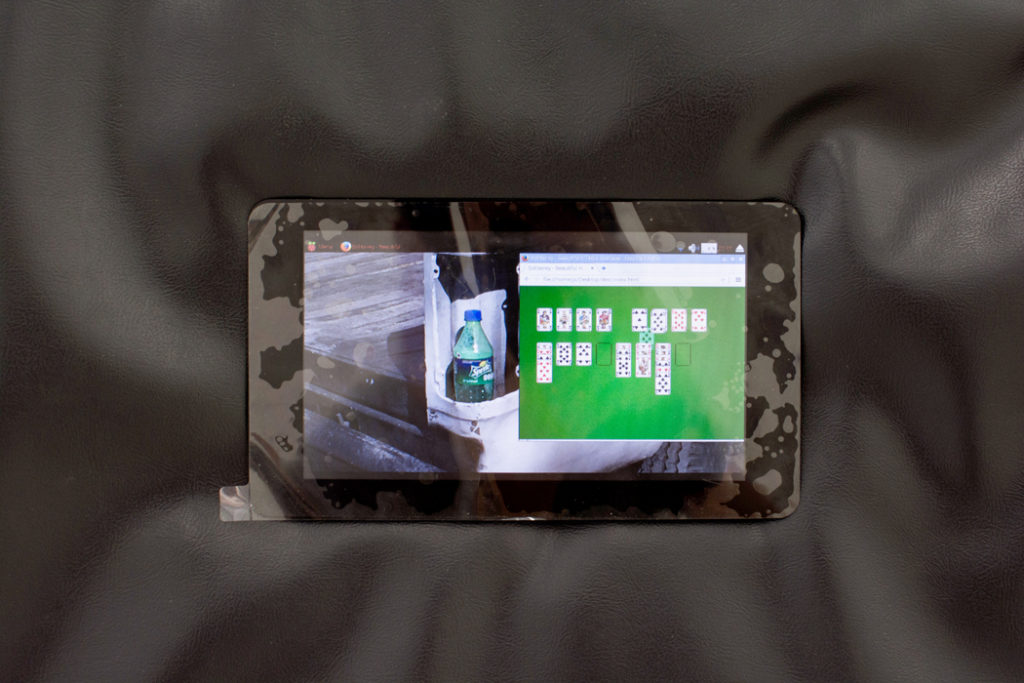

The “point” is a formula for art showing where its efficacy is evident, though still holed—work that is supposedly visceral, or based in the presence of a conceptual spectre that is somehow inarticulable though is cogent enough to be modularly not only understood but praised by a group of likeminded people. Take for example, a piece entitled “The Self-Aware Slug” consisting of a linux computer, custom software (a computer repeatedly beating solitaire), and vinyl: there I experience a rift between what has been denoted as “the idea” and what the object is actually doing (or the acknowledged awareness that the object will do something). Here the artwork is first a conceptual poem, and second an object.

The “point” becomes worrisome when, within the rift between the expected and the actual, a recognition of something that would otherwise compromise the idea is displaced by that same idea. Perhaps it is a matter of not being given enough information, however, when I say that this exhibition is about a ‘thing,’ it is because, for me to go ahead and then guess or assume what this thing may be would further regulate that which I am suggesting this exhibition is abusing. And that is something a viewer may need to question more, to which role am I fulfilling? Am I a decider or a regulator?

Adrian Piper in “The Logic of Modernism” wrote about the malleability of the “aberration” that was Greenbergian formalism similarly.

Relative to these lines of continuity, the peculiarly American variety of modernism known as Greenbergian formalism is an aberration. Characterized by its repudiation of content in general and explicitly political subject matter in particular, Greenbergian formalism gained currency as an opportunistic ideological evasion of the threat of cold war McCarthyite censorship and red-baiting in the fifties.

This work is manipulative and can be manipulated because it is evading the responsibility of being a producer and is instead reliant on a conceptual spectre of sorts. It is evasive in its withholding of information that would otherwise allow a viewer to discern if the work is engaging in responsible production. Responsible production is a method of art showing or viewing that is aware, though not in full knowing, of an object’s trajectory as a producer. As the object is shown and seen it is multiplied and reproduced the same as a meme, each time altered, each recreation with its own condition of existence. The responsibly produced artwork does not have to be explicitly based in and around political subject matter, rather, there is a certain political action that accompanies this responsibility taken by both artist and viewer.

The sensual object and I cannot meet inside of me. Instead, our encounter occurs on the interior of the relation between me and the real tree (which must be indirect, but there is no need to complicate things here). When the tree and I somehow form a link, we become a new object; every relation forms a new real object. (Graham Harman)

With the initial object’s relational reproduction alongside a conversation being had by Graham Harman or even Tristan Garcia, it would not be so bizarre to talk about these sculptures similar to the way someone like Hito Steyerl or Steven Shaviro would discuss media or film. Film and music videos, like other media works, are also machines for generating affect, and for capitalising upon, or extracting value from, this affect. Would it follow if we take a text such as Steyerl’s In Defense of the Poor Image and switch out “poor image” with “sculpture featured on art viewer?”

The sculpture featured on art viewer is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation.

I bring this all up, because at The Squinter’s Watch, it is clear that the work is about this one thing, a notion that is ideally inarticulable, though still maintains a modular registration transpersonally, defended only by a few encapsulating words I wish not name but will (hiking, gaming, solemnity). The work may in actuality be evasive; the work may in fact be displacing some other thing behind a screen of familiarities, (modular hanging of wall-based works, an interesting manipulation of material, depictions of a feeling or lifestyle). This is most likely not an intention of the work, however, it evidences the fragility, or weak integrity of a bridge (or “point”). A lack of any supplemental artist statement and or formal press release only helps to create a conceptual shroud. The work may then be mutated somewhere in the process of reproduction and dissemination (being featured on art viewer, being posted to instagram, a promotion on facebook, a rearticulation of the exhibition with a friend over coffee, maybe possibly even seeing the work in situ), which in turn would, in a worst case scenario allow, the possible continued fetishization of blue-collar aesthetics or, say a weird strain of heteronormativity at the fault of the originary original. Even though the work may not be necessarily about that, that same fetishization then is further co-opted into a contemporary arts canon.

Daniel Penny in a New Inquiry essay entitled The Irrelevant and the Contemporary: Why is Poetry #Trending in Contemporary Art penned: To go the way of the Bernadette Corporation and attempt to make poetry more commodified, more in line with contemporary art’s market logic and formalist preoccupations is a mistake. Poetry’s slowness, difficulty, irrelevance — these qualities must be made into virtues. If we circle back to Agamben, poets who are out of step with the time are the most contemporary of all.

I feel almost as though Penny’s accusation and rightful assertion that the Bernadette Corporation’s poetry is “more in line with contemporary art’s market logic,” is somehow skewed by the same idealism that conceptually sponsors this show. The dichotomization between the work and that which may compromise it is clear in art that decides it would rather discuss things supposedly beyond the cusp of any articulation (viscerality, the spectre, etc), or beyond the commensurability of an economic sphere. Although ‘‘the essence of culture is discrimination,’’ as Igor Kopytoff has put it, the market turns art into a homogeneous commodity whose value is in no sense unique. (Olav Velthuis “The Symbolic Meaning of Prices Constructing the Value of Contemporary Art in Amsterdam and New York Galleries”.) The work in this show seems to be instituting this same dichotomization, or at the very least it is trying to sweep some of the contextual parameters that may compromise the work, under the rug. The term post-object (seemingly endorsed by Penny) here only sounds to me as an evasive maneuver as to avoid responsibility for any ‘negative production’ of the sculpture as object. Or, it is to convince me that that aspect of the work simply does not matter.

Maybe the work needs to be contaminated in order to allow for the safer dispersing and fracturing of the art. The Bernadette Corporation, Christopher Ho, Nandi Loaf, or even Puppies Puppies are all great examples of artists who allow the contamination of their own work. Further, if the work allows itself to be contaminated or compromised, it will also gift a viewer with the ability to place more trust in the hands of the artist himself. With this in mind, if, while the work is dispersing (not only digitally, but through the subsequent reproduction of relation), the work is manipulated to be a propagator of something bad, it is not the responsibility of the author himself.

Images courtesy of Springsteen Gallery. The Squinter’s Watch is on view from July 9 through August 13, 2016.