“Art is a terrible risk, and no one would do it if they didn’t believe in themselves. I’m not sure if I buy it, but the idea has been floated that we, who do this shit, hope that through this work we can maybe escape. Even if you have to hand in your meatsack at some point, your work will stand in for you later. It’s the deposit you put down. Pay the meat price and get in the art tube.” In Steve Kado’s short story accompanying Encoach, a two-person show featuring works by Keith J. Varadi and Georgia Dickie, he skeptically addresses motives for art making. Specifically, escapism and self-preservation become central themes.

A bird’s “hand” in the work, even hypothetically, is critical in creating meaningful dialogue around motive. The presence of bird labor displaces motive from self-aware artist to non-self-aware animal performing the same work. I am using this information to decode the significance of color-sorted pellets by canary and I think it’s safe to use the canary as a stand in for any bird or non-self-aware animal. Male bowerbirds build complex structures of various found objects and sticks, usually grouping disparate objects of like colors together in an effort to attract a mate.

Birds preserve their identity through population, while artists preserve identity through objectified perception (i.e. art). This interpretation poses new questions surrounding an artist’s motives, like “Who/What are they trying to attract through their work?” making attractiveness a key component on the path to self-preservation. For me, this is a much more interesting read than plain old bricolage. The canary is the strongest component of Dickie’s work, and I wish it were more explicit.

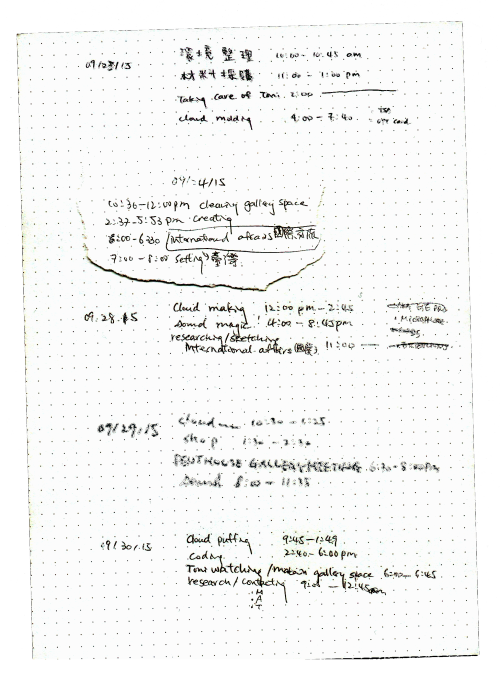

Steve Kado’s writing contains clues for decoding the work as well and clearly states his intentions for writing in the last couple lines, “Believe it or not, this piece started out as a reflection on the way primary accumulation and risk were interrelated. It was based very strongly on some ideas detected in the work. JSYK.” Just so you know: A casual way of presenting integral information.

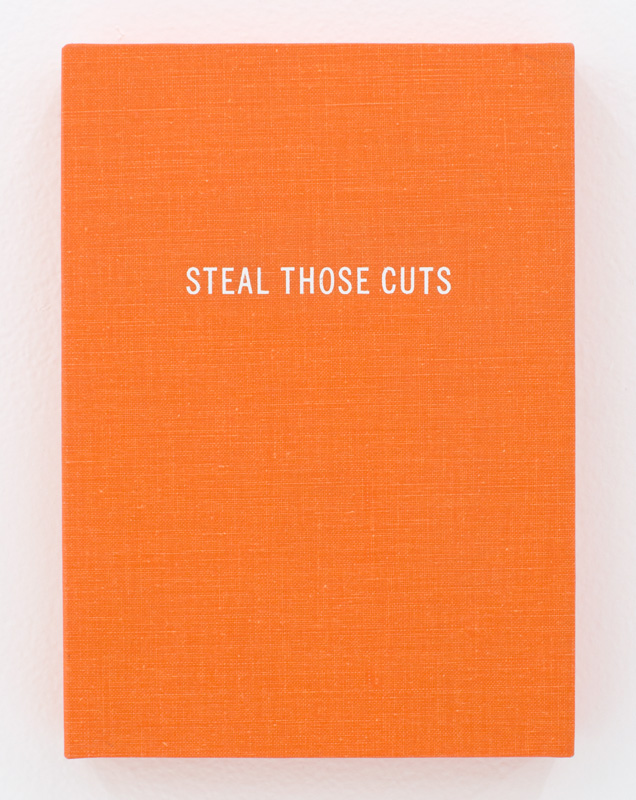

Oh, Hell; Past Gone; Grim Ripper; First Sight of Water; Regal Funk; Steal Those Cuts; Menagerie, PST; Foie Gras; World Truth; Live Like This; Maiden Man; Self-Help Writ Wrong. These phrases decorate 5×7 cloth panels by Varadi. An insider told me they are all titles of his poems, a detail that is not explicit, although it may be assumed or known by the artist’s friends. I almost expected full poems to be shown, considering Varadi’s reputation as a poet. The pieces mimic hardbound book covers, and are of varying cloth and ink color combinations. The colors are similarly rich, vibrant, and seductive, willing a longer pause from the viewer. The selection of this swatch of colors reminds me of Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays (1979-82) in which Holzer uses backgrounds of varying colors with black text, creating a visually stimulating support system for her provocative content. Varadi’s titles range from provocative (Self-Help Writ Wrong) to dramatized romantic (First Sight of Water), to absurd (World Truth).

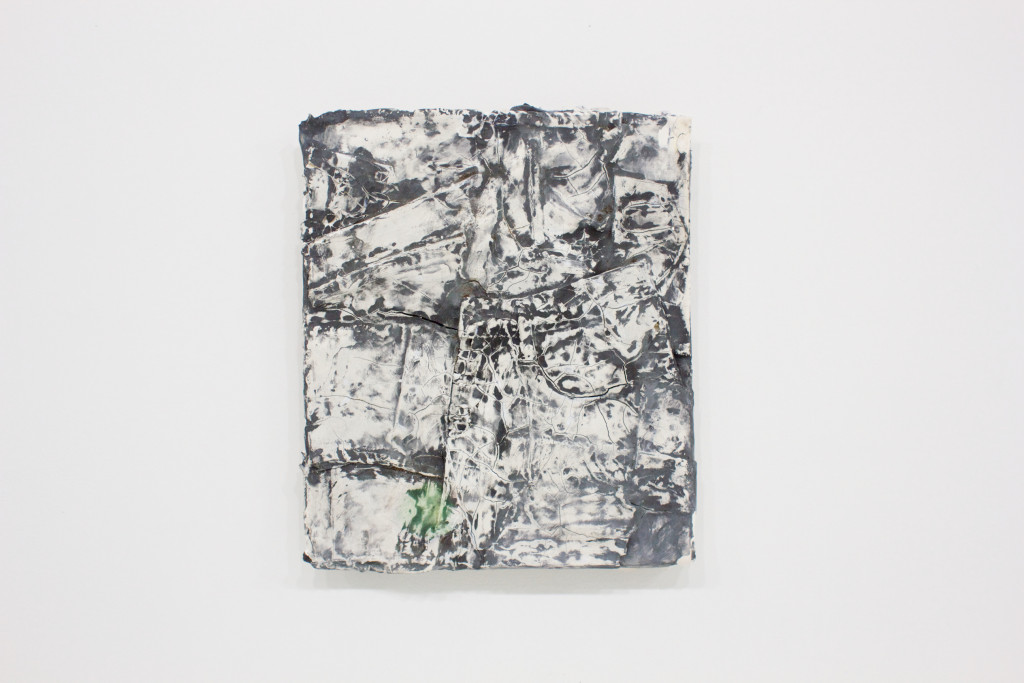

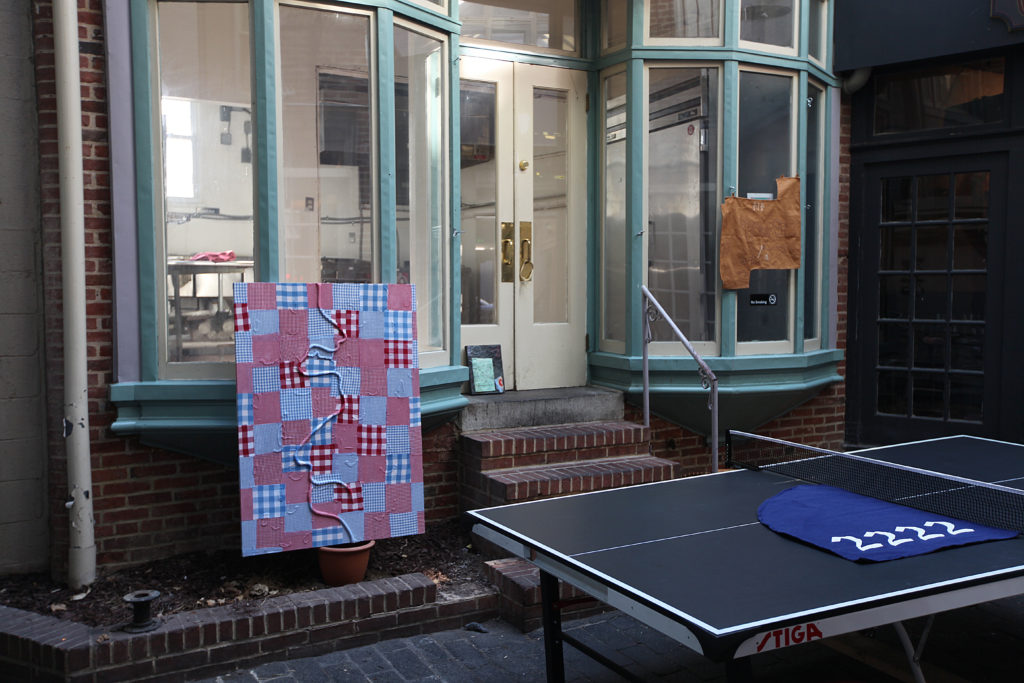

Dickie’s work is less literal. Near the back wall of the gallery, Pisetions (binders) stands displaying storage unit, metal, coral, wax, binders, rubber, and various found objects including some sort of midi splitter and chair parts. Not birdbrain bricolage, but regular. Objects are spatially redefined, perhaps for therapeutic purposes, but definitely not for attractiveness. Liminality exists between binder spiral spine and what looks like the molted shell of a 7 in. plasma ball. This piece did not captivate me in the same way as others by Dickie. The placement of the objects is too normalized, on display and restricted to even-numbered shelves. I over think the term “binder” in effort to read the piece. The shelving unit becomes a binder of objects, hollow glass balls become binders of air, electronic equipment becomes binder of signals, rubber becomes binder of tension, so on and so forth.

Adjacent is Declaration, a piece by Varadi, consisting of a narrow plinth covered in adhesive vinyl photographs, with a small bottle of crude oil placed on top, enclosed within an overturned pint glass. The photographs adhered to the plinth are snapshots reminiscent of nostalgic point-and-shoot collections. Most notably for me is an image of the word “PIG” with an X through it against a yellow wall. This type of image seems familiar, like I’ve seen this wall before or one like it, which I’m sure there are hundreds. The images seem to capture pauses in daily routine, and contain the motion found in street photography. There is an element of humor specific to the photographer, something that made them pause to chuckle to themselves. I read this as “Moments of Amusement decorate the sides of the structural support to the Eternal Rose of Industry.” Escapist antics are called out simply due to the fact that cars require gasoline to move. To get in your car and just go still requires a trip to Sunoco.

Turning to the wall we see Oasis, a Nevada license plate in a holder with state promotional text “I’d Rather Be Gambling In Las Vegas.” Through the lens of contemporary social media culture, this is a passé bottom-text meme. Again, escapism is on display.

A recurring vibe in both Varadi and Dickie’s work is a sentimental recognition of a fragmented object or place. This is clear in the centrally placed work Today Was a Rare Day (Many Minutes of Fun) by Dickie. Materials include metal birdcage perches, swing, blood, auxiliary cables, photographs, discarded canary feathers, doorknob, resurrection plant, and a disposable coffee cup. I research “resurrection plant” and find it resembles a brittle bird’s nest when dehydrated, but comes to life as a green fern when placed in water. Work that requires research creates an aura of depth both captivating and alienating. It attracts a type of viewer who is eager and has access to resources outside the gallery. The other kind of viewer dismisses the work as difficult or not of their taste.

After the opening, an artist friend of mine revealed her momentary panic when she thought she had absentmindedly rested her own coffee cup on top of the sculpture. I’m unsure how to appropriately define that sensation, but I believe it’s related to what Kado approaches when he writes, “So we aren’t changing individual identities in different contexts, but those contexts themselves define sets of behaviors and attitudes that are exchanged within, and all of those relationships are trans-individual.” Whose coffee cup is resting on the artwork? Is it the artworks? Does it belong to the artist who made the work? Or does it belong to the artist who left her studio to attend an art opening? Is it the gallerist’s? Did someone leave it there during the install, and it just stuck? Once again, Dickie makes us question possession.

Investigating self-preservation and escapism as motives for making art leads to some tricky conclusions. One idea is that artists preserve their identities post-mortem through work that is attractive enough to be cared for long term, that is, work attractive on multiple dimensions (visually, conceptually, socially, etc.) But being able to escape the normalities of daily routine enough to feel inspired involves an element of risk taking, which is contrary to self-preservation. Is it possible for an artist to create work that does not require an ounce of risk-taking, although the creation of art in itself is a risk?

Encoach is a great show for a viewer who likes to dig. The work can speak for itself, but it speaks tangentially. It lingers and leaves you asking questions with no discernible answers. One question I can’t seem to shake is “What happened to the canary?”

Encoach ran from September 10 through October 8, 2016 at Springsteen Gallery, 502 W. Franklin Street, Baltimore, MD. Images courtesy of Springsteen.

Historically, a push towards deskilling (and valuing the deskilled) came paired with political implications, as it pushed the artist’s identification with the laborer by demoting the artist’s perceived agency and by including the laborer in the artist’s methods

Historically, a push towards deskilling (and valuing the deskilled) came paired with political implications, as it pushed the artist’s identification with the laborer by demoting the artist’s perceived agency and by including the laborer in the artist’s methods